The terrible dream of Rodion Raskolnikov. Dreams in Dostoevsky's novel Crime and Punishment What is the meaning of Raskolnikov's first dream

Beating a horse in Raskolnikov's first dream

Raskolnikov sees his first dream shortly before the murder. Before falling asleep, he wanders around St. Petersburg for a long time and thinks about the usefulness of killing an old woman-pawnbroker who has outlived her life and "seizes" someone else's.

“Raskolnikov had a terrible dream. He dreamed of his childhood, back in their town. He is seven years old and walks on a holiday, in the evening, with his father outside the city. The time is gray, the day is suffocating, the terrain is exactly the same as it has survived in his memory: even in his memory it has become much more ironed out than it seemed now in a dream. The town stands openly, as if in the palm of your hand, not willow around; somewhere very far away, at the very edge of the sky, a forest is blackening. A few steps from the last city garden there is a tavern, a large tavern, which always made an unpleasant impression on him and even fear when he passed by him, walking with his father. There was always such a crowd, they shouted, laughed, swore, sang so ugly and hoarsely, and fought so often; such drunken and terrible faces were always wandering around the tavern ... When he met them, he pressed close to his father and trembled all over. Near the pub, the road, country roads, is always dusty, and the dust on it is always so black. She walks, meandering, further and three hundred steps around the city cemetery to the right. Among the cemetery there is a stone church with a green dome, to which he went twice a year with his father and mother to mass, when memorial services were served for his grandmother, who had died a long time ago and whom he had never seen. At the same time, they always took kutia with them on a white dish, in a napkin, and kutia was sugar made of rice and raisins pressed into the rice with a cross. He loved this church and the ancient images in it, for the most part without salaries, and the old priest with a trembling head. Near grandmother's grave, on which there was a slab, there was also a small grave of his younger brother, who had died for six months and whom he also did not know at all and could not remember; but he was told that he had a little brother, and every time he visited the cemetery, he religiously and respectfully baptized over the grave, bowed to her and kissed her. And now he is dreaming: they are walking with their father on the road to the cemetery and pass by the pub; he holds his father's hand and looks back with fear at the pub. A special circumstance attracts his attention: this time it’s like a promenade, a crowd of dressed-up bourgeois women, women, their husbands and all kinds of rabble. Everyone is drunk, everyone is singing songs, and there is a cart near the inn's porch, but a strange cart. This is one of those large carts that harness large draft horses and transport goods and wine barrels in them. He always liked to look at these huge draft horses, long-maned, with thick legs, walking calmly, with a measured step and carrying some whole mountain behind them, not at all embracing, as if it was even easier for them with carts than without carts. But now, strangely enough, a small, skinny, gray-haired peasant nag was harnessed to such a large cart, one of those that - he often saw this - sometimes tear himself apart with a high cartload of firewood or hay, especially if the cart gets stuck in the mud or in a rut, and at the same time they are so painful, the peasants always beat them so painfully with whips, sometimes even in the face and in the eyes, but he is so sorry, so sorry to see it that he almost cries, and mother always used to , takes him away from the window. But then suddenly it becomes very noisy: they come out of the tavern with shouts, with songs, with balalaikas, drunken, drunken big men in red and blue shirts, with saddle stitches. “Sit down, everyone sit down! - shouts one, still young, with such a thick neck and with a fleshy, red as a carrot, face, - I'll take everyone, sit down! " But immediately there is laughter and exclamations:

That kind of nag, yes you are lucky!

Yes, you, Mikolka, in your mind, or something: you put such a mare in such a cart!

But Savraska will certainly be twenty years old, brothers!

Sit down, I'll take everyone! - Mikolka shouts again, jumping first into the cart, takes the reins and stands on the front end to his full height. - Bay dave with Matvey left, - he shouts from the cart, - and the mare etta, brothers, only my heart breaks: so, it seems, he killed her, she eats bread for nothing. I say sit down! Jump comin! Jump will go! - And he takes the whip in his hands, with pleasure preparing to whip the savraska.

Yes, sit down, what! - they laugh in the crowd. - Hey, he'll go galloping!

She hasn't jumped for ten years already.

Jumping!

Do not regret, brothers, take all whips, cook!

And then! Seize her!

Everyone climbs into Mikolka's cart with laughter and witticisms. Six people climbed, and you can still plant. They take with them one woman, fat and ruddy. She is wearing red calico, in a kitsch with beads, cats on her legs, snaps nuts and chuckles. All around in the crowd they are also laughing, and indeed, how can one not laugh: it’s like a dashing mare and such a burden to ride at a gallop! The two guys in the cart immediately take a whip to help Mikolka. You hear: "Well!" Laughter in the cart and in the crowd doubles, but Mikolka gets angry and in a rage whips the mare with frequent blows, as if she really thinks that she will go at a gallop.

Let me go, brothers! - shouts one guy from the crowd who has burst into tears.

Sit down! Everybody sit down! - shouts Mikolka, - everyone will be lucky. I'll spot! - And it whips, whips, and no longer knows what to beat from the frenzy.

Daddy, daddy, - he shouts to his father, - daddy, what are they doing? Daddy, the poor horse is being beaten!

Let's go, let's go! - says the father, - drunk, playing naughty, fools: let's go, don't look! - and wants to take him away, but he breaks free from his hands and, not remembering himself, runs to the horse. But the poor horse is bad. She gasps, stops, twitches again, almost falls.

Seek to death! - shouts Mikolka, - for that matter. I'll spot!

Why is there a cross on you, or what, no, devil! - shouts one old man from the crowd.

It has been seen that such a horse carried such a load, - adds another.

Freeze! shouts a third.

Don't touch! My goodness! I do what I want. Sit down again! Everybody sit down! I want you to gallop without fail! ..

Suddenly laughter is heard in one gulp and covers everything: the mare could not bear the frequent blows and began to kick in powerlessness. Even the old man could not resist and grinned. And indeed: that kind of dashing mare, and also kicks!

Two guys from the crowd get another whip and run to the horse to whip it from the sides. Everyone runs from their side.

In her face, whip in her eyes, in her eyes! - shouts Mikolka.

A song, brothers! - shouts someone from the cart, and everyone in the cart picks up. A riotous song is heard, a tambourine rattles, a whistle in the refrains. The old woman snaps nuts and chuckles.

... He runs beside the horse, he runs ahead, he sees how it is flogged in the eyes, in the very eyes! He is crying. The heart in him rises, tears flow. One of the secants touches him in the face; he does not feel, he breaks his arms, shouts, rushes to the gray-haired old man with a gray beard, who shakes his head and condemns all this. One woman takes him by the hand and wants to take him away; but he breaks free and again runs to the horse. She already with the last effort, but once again begins to kick.

And so that those devil! - exclaims Mikolka in rage. He throws the whip, bends down and pulls out a long and thick shaft from the bottom of the cart, takes it by the end in both hands and swings it with effort over the Savraska.

Will pique! - they shout around.

My goodness! - shouts Mikolka and lowers the shaft with all his might. A heavy blow is heard.

And Mikolka swings another time, and another blow with all its might falls on the back of the unfortunate nag. She sinks all backwards, but jumps up and pulls, pulls with all her last strength in different directions in order to take out; but from all sides they take it in six whips, and the shaft again rises and falls for the third time, then for the fourth, measuredly, with a swing. Mikolka is furious that he cannot kill with one blow.

Hardy! - they shout around.

Now it will inevitably fall, brothers, here it will end! one amateur shouts from the crowd.

With her ax, what! End her at once, ”the third shouts.

Eh, eat those mosquitoes! Make way! - Mikolka cries out furiously, throws the shaft, bends down into the cart again and pulls out an iron crowbar. - Watch out! - he shouts, and with all his might he stuns his poor horse. The blow collapsed; the mare staggered, settled down, was about to pull, but the crowbar again falls with all its might on her back, and she falls to the ground, as if all four of her legs had been cut at once.

Finish off! - Mikolka shouts and jumps up, as if he doesn’t remember himself, from the cart. Several guys, also red and drunk, grab whatever they find - whips, sticks, a shaft, and run to the dying mare. Mikolka stands to the side and starts hitting the back with a crowbar in vain. The nag stretches out its muzzle, sighs heavily and dies.

Finished it! - shout in the crowd.

And why didn’t she ride!

My goodness! - shouts Mikolka, with a crowbar in his hands and with bloodshot eyes. He stands as if regretting that there is no one else to beat.

Well, really, you know, there is no cross on you! - many voices are already shouting from the crowd.

But the poor boy no longer remembers himself. With a cry he makes his way through the crowd to Savraska, grabs her dead, bloody muzzle and kisses her, kisses her in the eyes, on the lips ... Then he suddenly jumps up and in a frenzy rushes with his fists at Mikolka. At that moment, his father, who had been chasing him for a long time, grabs him at last and carries him out of the crowd.

Let's go to! let's go to! - he says to him, - let's go home!

Daddy! Why did they ... the poor horse ... killed! - he sobs, but his breath catches, and the words cries out from his cramped chest.

Drunk, playing naughty, none of our business, let's go! - says the father. He wraps his arms around his father, but his chest is cramping, cramping. He wants to catch his breath, scream, and wakes up.

He woke up drenched in sweat, hair damp with sweat, panting, and stood up in horror.

“Thank God, this is only a dream! he said, sitting down under a tree and taking a deep breath. - But what is it? Could it be that a fever is beginning in me: such an ugly dream! "

His whole body was, as it were, broken; vague and dark at heart. He put his elbows on his knees and rested his head with both hands.

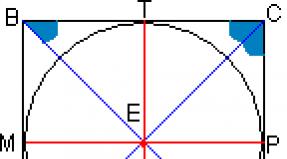

Raskolnikov sees his first dream, falling asleep in the bushes in the park after the "test" and a difficult meeting with Marmeladov, shortly before the murder of the old woman-pawnbroker - "lice ... useless, disgusting, pernicious", as he himself calls her after. Sleep is heavy, painful, exhausting and unusually rich symbols: Raskolnikov-boy loves to go to church, which personifies the heavenly principle on earth, that is, spirituality, moral purity and perfection; however, the road to the church passes by a tavern, which the boy does not like; a tavern is that terrible, worldly, earthly thing that destroys a person in a person. In the scene at the tavern - the murder of a helpless horse by a crowd of drunken men - little Raskolnikov tries to protect the unfortunate animal, screams, cries; here it is clear that by nature he is not at all cruel, ruthlessness and contempt for someone else's life, even for a horse, are alien to him and possible violence against a human person is disgusting, unnatural for him. It is significant that after this dream Raskolnikov does not see dreams for a long time, except for the vision on the eve of the murder - a desert and in it an oasis with blue water; it uses the traditional color symbolism: blue - the color of purity and hope, uplifting a person; Raskolnikov wants to get drunk, which means that everything is not lost for him yet, there is an opportunity to abandon the "experiment on himself."

Raskolnikov's tragic dream could have been inspired Dostoevsky text Nekrasov from his poem "On the Weather":

"Under the hard hand of a man

Slightly alive, skinny ugly,

The crippled horse is straining

Dragging an unbearable burden.

So she staggered and stood.

"Well!" - the driver grabbed the log

(the whip seemed to him not enough) -

And he beat her, beat her, beat her!

And running forward, on the shoulder blades

And in crying meek eyes!

All in vain. The nag was standing ... "

Beating a horse to death is not just Russian fun. Take a look at an episode from Hans Christian Andersen's story "Little Klaus and Big Klaus", written in 1835.

- Here I will urge you on your horses! Said Big Klaus.

He took the butt, which is used to hammer stakes into the field to leash horses, and so grabbed Little Klaus's horse that he killed it outright.

- Eh, now I don't have a single horse! - said Little Klaus and began to cry.

Then he took the hide from the horse, dried it thoroughly in the wind, put it in a sack, put the sack on his back and went into the city to sell the hide.

("Little Klaus and Big Klaus", G.H. Andersen)

In the Anglo-Saxon and German mentality, much more brutal than the Russian character, killing a horse with a butt is an ordinary event and by no means a reason for a nightmare. These sensitive Russian people, like Raskolnikov, have been raving about atrocious scenes for years and decades, attributing symbolic diabolical meanings to them, and the Western European "Klaus", having sobbed over the body of a dead horse, skinned it and quickly took it to the market. It was enough for the "terrible" realist writer Dostoevsky to kill one horse with the hands of insane, violent drunks, but the storyteller Andersen killed one horse with the hands of the most sober and economical burgher out of spiteful ambition, and four more out of greed.

- That's a thing! - said Big Klaus and immediately ran to Little Klaus.

- Where did you get so much money?

“I sold my horse hide last night.

- I sold it for a profit! - said Big Klaus, ran home, took an ax and killed all four of his horses, took off their skins and went to the city to sell.

- Skins! Skins! Who needs skins! He shouted through the streets.

In Russia, the horse is killed by drunken marginals, and in Europe - by "respectable" burghers. In our country, they kill at least to some extent on a motivated basis (the nag could not pull an overloaded cart and thus “disgraced” the owner), and in Europe, strong horses are killed - during plowing! - purely for human ambition and greed. And after that, for a century and a half, the whole of Europe is "frightened" by Raskolnikov's crime, ascribes to the Russian people a natural predisposition to committing crimes? The Euro-hypocrites that Dostoevsky hated so much. But back to Raskolnikov's dream.

In it, the details of the beating are transformed to the level of monstrous fiction, which is facilitated by many specific details. The episode depicting the beating and then the murder of a horse (in the novel it takes just over four pages) grows to the level of an incredible phantasmagoria, in which everything is real and at the same time fantastic.

Old woman-pawnbroker

This " horrible dream”, An excerpt from childhood - it would seem, the very, that is, that is a bright, kind and wonderful period of human life - but this is not what we feel when we read the lines about beating a horse. The reader sees the scene of the murder of a horse through the eyes of a seven-year-old boy who will forever remember the embodiment of cruelty. Yu.F. Karjakin, recalling his teaching practice, telling about how he asked a written "problem" in the lesson: "What is the meaning of Raskolnikov's first dream?" The teacher was struck by the exact answer of one of the students: "This dream is a cry of human nature against murder."

The beating of an animal once again reminds the protagonist of the novel about violence in the world, strengthens his belief in the correctness of his theory, which he nurtured, being in a sick state and dreaming of the “role of the ruler,” “Napoleon”. Raskolnikov does not see the difference between man and animal. In the form of a horse, he again sees humiliated and insulted people. In this dream, the word "ax" is mentioned several times, and this is not accidental: an ax is a symbol, it is a murder weapon, but not only a horse "With her ax, what! Finish her at once, ”but the old women are already in the real world. Little Rodion, already at the age of seven, is trying to restore justice, waving his fists: “in a frenzy he rushes with his fists at Mikolka,” but it's too late ... the horse is dead. And this means that his efforts alone are too little to change the consciousness of people, to eradicate the instinct of self-destruction of mankind. The abundance of violence in this dream was another impetus that forced Raskolnikov to commit murder. Unjust violence against animals strengthens Raskolnikov in the correctness of his theory. The world is cruel. Putting an overwhelming task in front of the horse, she was killed for not following the order. As Mikolka kills his horse (“my goodness, I want to do it ...”), so Raskolnikov kills the old woman mercilessly (“am I a trembling creature or have the right”).

Instrument for the transmigration of souls, according to Rodion Raskolnikov

Think about it at the right time

An alternative to the 2-year Higher Literary Courses and the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow, where they study for 5 years full-time or 6 years in absentia, is the Likhachev School of Writing. In our school, the basics of writing are purposefully and practically taught in only 6-9 months, and even less if the student wishes. Come on in: Spend just a little money and get up-to-date writing skills and get sensible discounts on editing your manuscripts.

The instructors at the Likhachev Private School of Writing Skills will help you avoid self-harm. The school works around the clock, seven days a week.

Rodion Raskolnikov, as you know, came up with his own theory, dividing people into "trembling creatures" and "having the right", thereby allowing "blood according to conscience." Throughout the entire work, the inconsistency of this hypothesis is proved. Dreams are one of the author's outstanding tools in the fight against the ideology of hatred. They are symbols, the decoding of which is the key to understanding Dostoevsky's complex and multi-tiered design.

- About a slaughtered horse... Already the first dream of the protagonist shows his true features and reveals his ability to compassion. Raskolnikov is transported to childhood, sees a horse being beaten with a whip by brutalized people. This episode proves the ambiguity of the character of the young theorist, who, empathizing with the poor animal in his dream, is actually preparing to kill a person. This dream becomes a symbolic expression of a world overflowing with violence, suffering and evil. It contrasts the tavern, as the personification of an ugly, base world, and the church, with which Raskolnikov has sad but bright memories. The motive of salvation from the terrible world of reality with the help of faith will continue to be traced throughout the novel.

- About Africa... Shortly before the fatal act, Raskolnikov dreamed of Africa in a dream. He sees an oasis, golden sand and blue water, which is a symbol of purification. This dream is the antithesis of the dreadful Everyday life hero. An important detail is that Rodion dreams of Egypt. In this regard, the motive of Napoleonism appears in a dream. The Egyptian campaign was one of the first undertaken by Napoleon. But there the emperor was in for a failure: the army was struck by the plague. So the hero is not awaiting a triumph of will, but disappointment in the finale of his own campaign.

- About Ilya Petrovich... After the murder of the old woman-pawnbroker, the young man is in a fever. The fever provokes two more dreams. The first of them is about Ilya Petrovich, who beats up the owner of a rented apartment, Rodion. It shows that Raskolnikov does not tolerate bullying a person, no matter how bad he is. It is also easy to understand that Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov has a fear of formal punishment (the law). This fact is embodied in the figure of a policeman.

- About the laughing old woman... Raskolnikov returns to the scene of the crime, where the murder he committed is almost repeated. The difference is that this time the old woman was laughing, mocking the hero. This may indicate that by killing the old woman, he ruined himself. Frightened, Raskolnikov flees from the scene of the crime. In this dream, Rodion feels the horror of exposure and the shame that torments him in reality. In addition, this nightmare confirms that the main character was morally incapable of killing, it was painfully perceived by him and became the reason for his further moral self-destruction.

- Sleep in hard labor... The last dream of the hero finally confirms the inconsistency of Rodion's hypothesis. “In his illness, he dreamed that the whole world was condemned as a victim of some terrible, unheard of and unprecedented plague plague” - the killer sees how his plan to “save” everything that exists is being realized, but in practice it looks terrible. As soon as, thanks to sophistic speculative reasoning, the line between good and evil disappears, people plunge into chaos and lose moral foundations on which society is based. The dream is contrasted with the theory: the hero believed that “unusually few people are born with a new thought,” and in the dream it is said that the world is crumbling from a lack of “pure people”. Thus, this dream contributes to Raskolnikov's sincere repentance: he understands that what is needed is not pretentious philosophizing from the onion, but sincere and good deeds opposed to evil and vice.

Svidrigailov's dreams

Svidrigailov is a character who also dreams symbolic dreams imbued with deep meaning. Arkady Ivanovich is a man fed up with life. He is equally capable of both cynical and dirty deeds, and noble ones. Several crimes are on his conscience: the murder of his wife and the suicide of the servant and the girl he insulted, who was only 14 years old. But his conscience does not bother him, only dreams convey the hidden side of his soul, unknown to the hero himself, it is thanks to his dreams that Arkady Ivanovich begins to see all his meanness and insignificance. There he beholds himself or the reflection of his qualities, which terrify him. In total, Svidrigailov sees three nightmares, and the line between dream and reality is so blurred that it is sometimes difficult to understand whether it is a vision or reality.

- Mice... In the first dream, the hero sees mice. The mouse is considered the personification of the human soul, an animal that quickly and almost imperceptibly escapes, like a spirit at the moment of death. In Christian Europe, the mouse was a symbol of evil, destructive activity. Thus, we can come to the conclusion that in Svidrigailov's dream the rodent is a harbinger of trouble, the inevitable death of the hero.

- About a drowned girl. Arkady Ivanovich sees a suicide girl. She had "an angelically pure soul that pulled out the last cry of despair, not heard, but impudently mocked in a dark night ...". It is not known exactly, but there were rumors about Svidrigailov that he seduced a fourteen-year-old girl. This dream seems to describe the hero's past. It is possible that it is after this vision that his conscience awakens, and he begins to realize the whole baseness of the actions from which he previously received pleasure.

- About a five-year-old girl... In the last, third dream, Svidrigailov has a dream about a little girl, whom he helps without any malicious intent, but suddenly the child transforms and begins to flirt with Arkady Ivanovich. She has an angelic face, in which the essence of a base woman is gradually emerging. She has a deceptive beauty that outwardly covers the soul of a person. This five-year-old girl reflected all the lasciviousness of Svidrigailov. This frightened him the most. In the image of demonic beauty, one can see a reflection of the duality of the character of the hero, a paradoxical combination of good and evil.

Waking up, Arkady Ivanovich feels his complete spiritual exhaustion and understands: he has no strength and desire to live on. These dreams reveal the hero's complete moral bankruptcy. And, if the second dream reflects an attempt to resist fate, then the last one shows all the ugliness of the hero's soul, from which there is no escape.

The meaning and role of dreams

Dostoevsky's dreams are a bare conscience, not spelled out by any soothing, glorious words.

Thus, in dreams, the true characters of the heroes are revealed, they show what people are afraid to admit even to themselves.

Interesting? Keep it on your wall!Raskolnikov had a terrible dream. He dreamed of his childhood, back in their town. He is seven years old and walks on a holiday, in the evening, with his father outside the city. The time is gray, the day is suffocating, the terrain is exactly the same as it has survived in his memory: even in his memory it has become much more ironed out than it seemed now in a dream. The town stands openly, as if in the palm of your hand, not willow around; somewhere very far away, at the very edge of the sky, a forest is blackening. A few steps from the last city garden there is a tavern, a large tavern, which always made an unpleasant impression on him and even fear when he passed by him, walking with his father. There was always such a crowd, they shouted, laughed, swore, sang so ugly and hoarsely, and fought so often; such drunken and terrible faces were always wandering around the tavern ... When he met them, he pressed close to his father and trembled all over. Near the pub there is a road, a country road, always dusty, and the dust on it is always so black. She walks, meandering, further and three hundred steps around the city cemetery to the right. In the middle of the cemetery is a stone church with a green dome, to which he went twice a year with his father and mother to mass, when memorial services were served for his grandmother, who had died a long time ago and whom he had never seen. At the same time, they always took kutia with them on a white dish, in a napkin, and kutia was sugar made of rice and raisins pressed into the rice with a cross. He loved this church and the ancient images in it, for the most part without salaries, and the old priest with a trembling head. Near grandmother's grave, on which there was a slab, there was also a small grave of his younger brother, who had died for six months and whom he also did not know at all and could not remember: but he was told that he had a little brother, and every time he visited cemetery, religiously and respectfully baptized over the grave, bowed to her and kissed her. And now he is dreaming: they are walking with their father on the road to the cemetery and pass by the pub; he holds his father's hand and looks back with fear at the pub. A special circumstance attracts his attention: this time it’s like a promenade, a crowd of dressed-up bourgeois women, women, their husbands and all kinds of rabble. Everyone is drunk, everyone is singing songs, and there is a cart near the inn's porch, but a strange cart. This is one of those large carts that harness large draft horses and transport goods and wine barrels in them. He always liked to look at these huge draft horses, long-maned, with thick legs, walking calmly, with a measured step and carrying some whole mountain behind them, not at all embracing, as if it was even easier for them with carts than without carts. But now, strangely enough, a small, skinny, greedy peasant nag was harnessed to such a large cart, one of those who - he often saw this - sometimes tear himself apart with a high cartload of firewood or hay, especially if the cart gets stuck in the mud or in a rut, and at the same time they are so painful, they are always beaten so painfully by the peasants with whips, sometimes even in the face and in the eyes, and he is so sorry, so sorry to see it that he almost cries, and mother always used to takes him away from the window. But then suddenly it becomes very noisy: they come out of the tavern with shouts, with songs, with balalaikas, drunken, drunken big men in red and blue shirts, with saddle stitches. “Sit down, everyone sit down! - shouts one, still young, with such a thick neck and a fleshy face, red as carrots, - I'll take everyone, sit down! " But immediately there is laughter and exclamations:

- That kind of nag, yes you are lucky!

- Yes, you, Mikolka, in your mind, or something: you put such a mare in such a cart!

- But Savraska will certainly be twenty years old, brothers!

- Sit down, I'll take everyone! - Mikolka shouts again, jumping first into the cart, takes the reins and stands on the front end at full height. “The bay dave with Matvey left,” he shouts from the cart, “but the little mare, brothers, only breaks my heart: it would seem that he killed her, she eats bread for nothing. I say sit down! Jump comin! Jump will go! - And he takes the whip in his hands, with pleasure preparing to whip the savraska.

- Yes, sit down, what! - they laugh in the crowd. - Hey, he'll go galloping!

“She hasn't jumped for ten years already.

- Jumping!

- Do not regret, brothers, take all whips, cook!

- And then! Seize her!

Everyone climbs into Mikolka's cart with laughter and witticisms. Six people climbed, and you can still plant. They take with them one woman, fat and ruddy. She is wearing red calico, in a kitsch with beads, cats on her legs, snaps nuts and chuckles. All around in the crowd they are also laughing, and indeed, how can one not laugh: it’s such a dashing filly and such a burden to ride at a gallop! The two guys in the cart immediately take a whip to help Mikolka. You hear: "Well!" The laughter in the cart and in the crowd doubles, but Mikolka gets angry and in a rage whips the filly with frequent blows, as if she really thinks that she will go at a gallop.

- Let me go, brothers! - shouts one guy from the crowd who has burst into tears.

- Sit down! Everybody sit down! - shouts Mikolka, - everyone will be lucky. I'll spot! - And it whips, whips, and no longer knows what to beat from the frenzy.

“Daddy, daddy,” he shouts to his father, “daddy, what are they doing! Daddy, the poor horse is being beaten!

- Let's go, let's go! - says the father, - drunk, playing naughty, fools: let's go, don't look! - and wants to take him away, but he breaks free from his hands and, not remembering himself, runs to the horse. But the poor horse is bad. She gasps, stops, twitches again, almost falls.

- Seki to death! - shouts Mikolka, - for that matter. I'll spot!

- Why is there a cross on you, or what, no, devil! - shouts one old man from the crowd.

“You've seen such a horse carrying such a load,” adds another.

- Freeze! Shouts a third.

- Do not trosh! My goodness! I do what I want. Sit down again! Everybody sit down! I want you to gallop without fail! ..

Suddenly laughter bursts out in one gulp and covers everything: the mare could not bear the frequent blows and began to kick in powerlessness. Even the old man could not resist and grinned. And indeed: that kind of a dashing filly, and also kicks!

Two guys from the crowd get another whip and run to the horse to whip it from the sides. Everyone runs from their side.

- In the face of her, whip in the eyes, in the eyes! - shouts Mikolka.

- Song, brothers! - shouts someone from the cart, and everyone in the cart picks up. A riotous song is heard, a tambourine rattles, a whistle in the refrains. Babenka snaps nuts and chuckles.

... He runs beside the horse, he runs ahead, he sees how it is flogged in the eyes, in the very eyes! He is crying. The heart in him rises, tears flow. One of the secants touches him in the face; he does not feel, he breaks his hands, shouts, rushes to the gray-haired old man with a gray beard, who shakes his head and condemns all this. One woman takes him by the hand and wants to take him away; but he breaks free and again runs to the horse. She already with the last effort, but once again begins to kick.

- And so that those devil! - exclaims Mikolka in rage. He throws the whip, bends down and pulls out a long and thick shaft from the bottom of the cart, takes it by the end in both hands and swings it with effort over the Savrask.

- Will pique! - they shout around.

- My good! - shouts Mikolka and lowers the shaft with all his might. A heavy blow is heard.

And Mikolka swings another time, and another blow with all its might falls on the back of the unfortunate nag. She sinks all backwards, but jumps up and jerks, pulls with all her last strength in different directions in order to take out; but from all sides they take it in six whips, and the shaft again rises and falls a third time, then a fourth, measuredly, with a swing. Mikolka is furious that he cannot kill with one blow.

- Hardy! - they shout around.

- Now it will certainly fall, brothers, here it will end! One amateur shouts from the crowd.

- With her ax, what! End her at once, ”the third shouts.

- Eh, eat those mosquitoes! Make way! - Mikolka cries out furiously, throws the shaft, bends down into the cart again and pulls out an iron crowbar. - Watch out! - he shouts, and with all his might he stuns his poor horse. The blow collapsed; the mare staggered, settled down, was about to jerk, but the crowbar again falls with all its might on her back, and she falls to the ground, as if all four of her legs had been hit at once.

- Finish off! - Mikolka shouts and jumps up, as if he doesn’t remember himself, from the cart. Several guys, also red and drunk, grab whatever - whips, sticks, shafts - and run to the dying filly. Mikolka stands to the side and starts hitting the back with a crowbar in vain. The nag stretches out its muzzle, sighs heavily and dies.

- Finished! - shout in the crowd.

- Why didn’t she ride!

- My good! - shouts Mikolka, with a crowbar in his hands and with bloodshot eyes. He stands, as if regretting that there is no one else to beat.

- Well, really, to know, there is no cross on you! - many voices are already shouting from the crowd.

But the poor boy no longer remembers himself. With a cry he makes his way through the crowd to Savraska, grabs her dead, bloody face and kisses her, kisses her in the eyes, on the lips ... Then he suddenly jumps up and in a frenzy rushes with his fists at Mikolka. At that moment, his father, who had been chasing him for a long time, finally grabs him and carries him out of the crowd.

- Let's go to! let's go to! - he says to him, - let's go home!

- Daddy! Why did they ... the poor horse ... killed! - he sobs, but his breath catches, and the words are screaming out of his cramped chest.

- Drunk, playing naughty, none of our business, let's go! - says the father. He wraps his arms around his father, but his chest is cramping, cramping. He wants to catch his breath, scream, and wakes up.

He woke up drenched in sweat, hair damp with sweat, panting, and stood up in horror.

- Thank God, this is only a dream! He said, sitting down under a tree and taking a deep breath. - But what is it? Could it be that a fever is beginning in me: such an ugly dream!

His whole body was, as it were, broken; vague and dark at heart. He rested his elbows on his knees and rested his head with both hands.

- God! He exclaimed. hide, all covered in blood ... with an ax ... Lord, really?

He trembled like a leaf as he spoke.

The great master of the psychological novel, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, used a technique such as sleep for a deeper portrayal of his hero in the work "Crime and Punishment". With the help of dreams, the writer wanted to deeply touch the character and soul of a person who decided to kill. The main character novel, Rodion Raskolnikov, had four dreams. We will analyze the episode of Raskolnikov's dream, which he saw before the murder of the old woman. Let's try to figure out what Dostoevsky wanted to show with this dream, what is his main idea, how he is connected with real events in the book. We will also pay attention to the hero's last dream, which is called apocalyptic.

The Writer's Use of Sleep to Deeply Reveal the Image

Many writers and poets, in order to deeper reveal the image of their character, resorted to the description of his dreams. It is worth remembering Pushkin's Tatyana Larina, who in a dream saw a strange hut in a mysterious forest. By this, Pushkin showed the beauty of the soul of a Russian girl who grew up on old legends and fairy tales. The writer Goncharov managed to dip Oblomov into his childhood at night, to enjoy the serene paradise of Oblomovka. The writer devoted an entire chapter of the novel to this dream. Utopian features were embodied in the dreams of Vera Pavlovna Chernyshevsky (novel "What is to be done?"). With the help of dreams, writers bring us closer to the heroes, trying to explain their actions. The analysis of the episode of Raskolnikov's dream in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment is also very important. Without him, it would have been impossible to understand the restless soul of the suffering student who decided to kill the old woman-pawnbroker.

A brief analysis of Raskolnikov's first dream

So, Rodion saw his first dream after he decided to prove to himself that he was not "a trembling creature and has the right," that is, he dared to kill the hated old woman. Analysis of Rakolnikov's dream confirms that the very word "murder" frightened the student, he doubts that he will be able to do it. The young man is terrified, but still dares to prove that he belongs to the highest beings who have the right to shed "blood according to conscience." Raskolnikov is given courage by the idea that he will act as a noble savior for many poor and humiliated. Only here Dostoevsky, with the first dream of Rodion, breaks such reasoning of the hero, depicting a vulnerable, helpless soul, which is mistaken.

Raskolnikov dreams of childhood in his hometown. Childhood reflects a carefree period of life, when you do not need to make important decisions and be responsible for your actions. It is no accident that Dostoevsky brings Rodion back to childhood at night. This suggests that the problems adult life brought the hero to a depressed state, he tries to escape from them. The struggle between good and evil is also associated with childhood.

Rodion sees his father next to him, which is very symbolic. The father is considered a symbol of protection and safety. The two of them walk past the tavern, drunk men run out of it. Rodion watched these images every day on the streets of St. Petersburg. One peasant, Mikolka, took it into his head to ride the others on his cart, in the harness of which was an emaciated peasant nag. The whole company gets into the cart with pleasure. A frail horse is not able to pull such a load, Mikolka beats the nag with all his might. Little Rodion watches in horror as the horse's eyes fill with blood from the blows. The drunken crowd calls to finish her off with an ax. The frenzied owner finishes the nag. Raskolnikov the child is very scared, out of pity he rushes to the horse's defense, but with a delay. The intensity of passions reaches the limit. The vicious aggression of drunken men is opposed to the intolerable despair of the child. Before his eyes, a cruel murder of a poor horse took place, which filled his soul with pity for her. To convey the expressiveness of the episode, Dostoevsky puts an exclamation mark after each phrase, which helps to analyze Raskolnikov's dream.

What feelings are filled with the atmosphere of the first dream of Dostoevsky's hero?

The dream atmosphere is complemented by the strongest feelings. On the one hand, we see a malicious, aggressive, unbridled crowd. On the other hand, attention is paid to the unbearable despair of little Rodion, whose heart shakes with pity for the poor horse. But most of all, the tears and horror of the dying nag are impressive. Dostoevsky masterfully showed this terrible picture.

The main idea of the episode

What did the writer want to show with this episode? Dostoevsky focuses on the rejection of murder by human nature, including the nature of Rodion. Before going to bed, Raskolnikov thought that it would be useful to kill an old money-lender who had outlived her life and made others suffer. From the terrible scene seen in the dream, Raskolnikov was covered with cold sweat. So his soul struggled with reason.

When analyzing Raskolnikov's sleep, we are convinced that sleep does not have the property of obeying the mind, therefore, the nature of a person is visible in it. Dostoevsky's idea was to show with this dream Rodion's rejection of murder by his heart and soul. Real life, where the hero takes care of his mother and sister, wants to prove his theory about "ordinary" and "extraordinary" personalities, makes him commit a crime. He sees a benefit in killing that drowns out the torment of his nature. In the old woman, the student sees a useless, harmful creature that will soon die by itself. Thus, the writer put into the first dream the true reasons for the crime and the unnaturalness of the murder.

Connection of the first dream with further events of the novel

The first dream takes place in his hometown, which symbolizes St. Petersburg. Integral components Northern capital there were taverns, drunken men, a suffocating atmosphere. The author sees in St. Petersburg the cause and accomplice of Raskolnikov's crime. The atmosphere of the city, imaginary dead ends, cruelty and indifference so influenced the protagonist that they aroused a morbid state in him. It is this state that pushes the student to unnatural murder.

The harrowing in the soul of Raskolnikov after sleep

Rodion shudders after his dream, reinterprets it. Nevertheless, after mental anguish, the student kills the old woman and also Elizabeth, who resembles a downtrodden and helpless nag. She didn’t even dare to raise her hand to defend herself from the assassin’s ax. Dying, the old woman will say the phrase: "We drove the nag!". But in a real situation, Raskolnikov will already be an executioner, not a defender of the weak. He became part of a rough, cruel world.

Analysis of Raskolnikov's last dream

In the epilogue of the novel, readers see another dream of Rodion, it looks more like half-delirium. This dream already foreshadowed a moral recovery, getting rid of doubts. An analysis of Raskolnikov's (the latter's) dream confirms that Rodion has already found answers to questions about the collapse of his theory. Raskolnikov in his last dream saw the approach of the end of the world. The whole world plunged into a terrible disease and is about to disappear. Smart and strong-willed microbes (spirits) have spread around. They possessed people, making them crazy and deranged. Sick people considered themselves the smartest and justified all their actions. People humiliating each other were like spiders in a jar. Such a nightmare completely healed the hero spiritually and physically. He goes to new life where there is no monstrous theory.

The meaning of student dreams

The analysis of Raskolnikov's dreams in Crime and Punishment proves that in compositional terms they play an essential role. With their help, the reader draws attention to the plot, images, specific episodes. These dreams help to better understand the main idea of the novel. With the help of dreams, Dostoevsky very deeply and completely revealed the psychology of Rodion. If Raskolnikov had listened to his inner self, he would not have committed a terrible tragedy that split his consciousness into two halves.

Dostoevsky called his novel Crime and Punishment, and the reader has the right to expect that it will be a forensic novel, where the author will depict the history of the crime and criminal punishment. In the novel there is definitely the murder of an old woman pawnbroker by a beggar student Raskolnikov, his mental agony for nine days (this is how long the novel takes place), his repentance and confession. The reader's expectations seem to be justified, and yet Crime and Punishment does not look like a tabloid detective story in the spirit of Eugene Sue, whose works were very popular in Dostoevsky's time. "Crime and Punishment" is not a judicial, but a socio-philosophical novel, precisely due to the complexity and depth of its content, it can be interpreted in different ways.

In Soviet times, literary critics focused on the social problems of the work, repeating mainly the ideas of DI Pisarev from the article "Struggle for Life" (1868). In the post-Soviet era, there were attempts to reduce the content of "Crime and Punishment" to God-seeking: behind a detective intrigue, behind a moral question about a crime, the question of God is hidden. This view of the novel is also not new; it was expressed by V.V. Rozanov at the beginning of the 20th century. It seems that if you combine these extreme points of view, you get the most correct view of both the novel itself and its idea. It is from these two points of view that Raskolnikov's first dream should be analyzed (1, V).

It is known that the tragic dream of the protagonist resembles a poem by N.A. Nekrasov from the cycle "On the Weather" (1859). The poet draws an everyday urban picture: a skinny crippled horse is dragging a huge cart and suddenly got up, because she does not have the strength to go further. The driver grabs the whip and mercilessly slashes the nag along the ribs, legs, even eyes, then takes the log and continues his brutal work:

And he beat her, beat her, beat her!

Feet somehow spread wide,

All smoking, settling back,

The horse only sighed deeply

And she looked ... (this is how people look,

Submitting to wrong attacks).

The owner's "work" was rewarded: the horse went forward, but somehow sideways, trembling nervously, with the last bit of strength. Various passers-by watched the street scene with interest and gave advice to the driver.

Dostoevsky in his novel enhances the tragedy of this scene: in Raskolnikov's dream (1, V), drunken men beat a horse to death. The little horse in the novel is a small, skinny peasant nag with a gray hair. An absolutely disgusting sight is the drover, who from Dostoevsky gets the name (Mikolka) and a repulsive portrait: "... young, with such a thick neck and with a fleshy face red like a carrot." Drunk, drunk, he brutally, with pleasure, whips Savraska. Mikolka is helped to finish off the nag by two guys with whips, and the angry owner yells at them to whip in the eyes. The crowd at the pub with laughter watches the whole scene: on her like peas. " Dostoevsky whips up terrible details: the audience cackles, Mikolka goes berserk and pulls the shaft out of the bottom of the cart. The blows of sticks and whips cannot quickly finish off the horse: it "jumps up and pulls, pulls with all the last of its strength in different directions in order to take it out." Drunken Mikolka takes out an iron crowbar and hits the nag on the head; his torturers run up to the fallen horse and finish it off.

Nekrasov has only one young girl, who watched the beating of a horse from a carriage, felt sorry for the animal:

Here is a young, welcoming face,

Here is the handle, - the window opened,

And stroked the unfortunate nag

White handle ...

At the end of the scene, at the end of the scene from the crowd of spectators, they no longer shout out advice, but reproaches that there is no cross on Mikolka, but only a boy (Raskolnikov sees himself as such) runs among the crowd and asks first some old man, then his father to save the horse. When Savraska falls dead, he runs up to her, kisses her dead head, and then rushes with his fists at Mikolka, who, I must say, did not even notice this attack.

In the scene under analysis, Dostoevsky emphasizes the ideas necessary for the novel, which are not in Nekrasov's poem. On the one hand, the weak child expresses the truth in this scene. He cannot stop killing, although with his soul (and not with his mind) he understands injustice, the inadmissibility of reprisals against a horse. On the other hand, Dostoevsky raises the philosophical question of resistance to evil, the use of force against evil. This formulation of the question logically leads to the right to shed blood in general and is condemned by the author. However, in the scene described, the blood cannot be justified by anything; it cries out for revenge.

The dream reveals the character of Raskolnikov, who will become a murderer tomorrow. A poor student is a kind and gentle person, able to sympathize with other people's misfortunes. Such dreams are not dreamed of by people who have lost their conscience (Svidrigailov's nightmare dreams are about something else) or who have come to terms with the eternal and universal injustice of the world order. The boy who rushed at Mikolka was right, and his father, without even trying to intervene in the killing of the horse, behaves indifferently (the savraska still belongs to Mikolka) and cowardly: "Drunk, they are naughty, it's not our business, let's go!" Raskolnikov cannot agree with such a position in life. Where is the exit? Character, intelligence, desperate family circumstances - everything pushes the protagonist of the novel to resist evil, but this resistance, according to Dostoevsky, is directed along the wrong path: Raskolnikov rejects universal human values for the sake of human happiness! Explaining his crime, he says to Sonya: “The old woman is nonsense! The old woman is perhaps a mistake, it’s not the point! The old woman is just a disease ... I wanted to cross as soon as possible ... I didn't kill a person, I killed a principle! " (3, VI). Raskolnikov means that he violated the commandment "Thou shalt not kill!", On which human relations have been built from time immemorial. If this moral principle is abolished, people will interrupt each other, as is depicted in the hero's last dream in the epilogue of the novel.

In Raskolnikov's dream about a horse, there are several symbolic moments that connect this episode with the further content of the novel. The boy ends up at the tavern where the murder of the nag takes place by accident: he and his father went to the cemetery to bow to the grave of his grandmother and brother and enter the church with a green dome. He loved to visit her because of the kind priest and the special feeling that he experienced while in her. Thus, in a dream, a tavern and a church appear side by side as two extremes of human existence. Further, in a dream, the murder of Lizaveta is already predicted, which Raskolnikov did not plan, but was forced to commit by coincidence. The innocent death of the unfortunate woman in some details (someone from the crowd shouts to Mikolka about the ax) resembles the death of Savraska from a dream: Lizaveta “trembled like a leaf, trembling, and convulsions ran all over her face; raised her hand, opened her mouth, but still did not cry out and slowly, backwards, began to move away from him into the corner ... ”(1, VII). In other words, before Raskolnikov's crime, Dostoevsky shows that the hero's bold ideas about the superman will necessarily be accompanied by innocent blood. Finally, the image of a tortured horse appears at the end of the novel in the scene of the death of Katerina Ivanovna, who will utter her last words: "Enough! .. It's time! .. (...) Have gone to the nag! .. Tore it up!" (5, V).

For Raskolnikov, the dream of a horse was like a warning: the whole future crime is "encoded" in this dream, like an oak in an acorn. No wonder, when the hero woke up, he immediately exclaimed: "Will I really do this?" But Raskolnikov was not stopped by a warning dream, and he fully received all the suffering of the murderer and the disappointment of the theoretician.

Summing up, it should be noted that Raskolnikov's first dream in the novel occupies an important place on social, philosophical and psychological grounds. First, in the scene of the murder of the horse, painful impressions of the surrounding life are expressed, seriously wounding Raskolnikov's conscientious soul and giving rise to the legitimate indignation of any honest person. The boy's indignation in Dostoevsky can be contrasted with the cowardly irony of the lyrical hero in Nekrasov, who from a distance, without interfering, observes the beating of the unfortunate nag in the street.

Secondly, in connection with the dream scene, a philosophical question arises about counteracting the world's evil. How to fix the world? Blood must be avoided, Dostoevsky warns, since the path to the ideal is inextricably linked with the ideal itself, the abolition of universal human moral principles will only lead a person to a dead end.

Thirdly, the dream scene proves that pain for the weak and defenseless lives in the hero's soul. The dream already at the beginning of the novel testifies that the killer of the old woman borrower is not an ordinary robber, but a man of ideas, capable of both action and compassion.