Sumerian writing. The emergence of writing What are wedges in cuneiform

Sumerian cuneiform is part of the small heritage that remains after this. Unfortunately, most of the architectural monuments were lost. All that remained were clay tablets with unique writings on which the Sumerians wrote - cuneiform. For a long time it remained an unsolved mystery, but thanks to the efforts of scientists, humanity now has data about what the civilization of Mesopotamia was like.

Sumerians: who are they?

The Sumerian civilization (literal translation “black-headed”) is one of the very first to emerge on our planet. The very origin of a people in history is one of the most pressing issues: disputes among scientists are still ongoing. This phenomenon is even given the name “Sumerian question.” The search for archaeological data yielded little, so the main source of study became the field of linguistics. The Sumerians, whose cuneiform script is best preserved, began to be studied from the point of view of linguistic kinship.

Around 5 thousand years BC, settlements appeared in the valley and Euphrates in the southern part of Mesopotamia, which later grew into a powerful civilization. Archaeological finds indicate how economically developed the Sumerians were. Cuneiform writing on numerous clay tablets tells about this.

Excavations in the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk allow us to make an unambiguous conclusion that the Sumerian cities were quite urbanized: there were classes of artisans, traders, and managers. Outside the cities lived shepherds and peasants.

Sumerian language

The Sumerian language is a very interesting linguistic phenomenon. Most likely, he came to southern Mesopotamia from India. For 1-2 millennia, the population spoke it, but it was soon replaced by Akkadian.

The Sumerians still continued to use their native language in religious events, administrative work was carried out in it, and they studied in schools. This continued until the beginning of our era. How did the Sumerians write their language? Cuneiform was used precisely for this purpose.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to restore the phonetic structure of the Sumerian language, because it belongs to the type where the lexical and grammatical meaning of a word lies in numerous affixes attached to the root.

Evolution of cuneiform

The emergence of Sumerian cuneiform coincides with the beginning of economic activity. It is due to the fact that it was necessary to record elements of administrative activity or trade. It should be said that Sumerian cuneiform is considered the first writing to appear, which provided the basis for other writing systems in Mesopotamia.

Initially, digital values were recorded while they were far from written language. A certain amount was indicated by special clay figurines - tokens. One token - one item.

With the development of economics, this became inconvenient, so they began to make special markings on each figure. Tokens were stored in a special container on which the owner’s seal was depicted. Unfortunately, in order to count the items, the storage had to be broken down and then sealed again. For convenience, information about the contents began to be depicted next to the seal, and after that the physical figures disappeared completely - only the prints remained. This is how the first clay tablets appeared. What was depicted on them was nothing more than pictograms: specific designations of specific numbers and objects.

Later, pictograms began to reflect abstract symbols. For example, a bird and an egg depicted next to it already indicated fertility. Such writing was already ideographic (signs-symbols).

The next stage is the phonetic design of pictograms and ideograms. It should be said that each sign began to correspond to a certain sound design that has nothing to do with the depicted object. The style is also changing, it is being simplified (we’ll tell you how later). In addition, for convenience, the symbols unfold and become horizontally oriented.

The emergence of cuneiform gave impetus to the replenishment of the dictionary of styles, which is happening very actively.

Cuneiform: Basic Principles

What was cuneiform writing? Paradoxically, the Sumerians could not read: the principle of writing was not the same. They saw the written text, because the basis was

The style was largely influenced by the material on which they wrote - clay. Why she? Let's not forget that Mesopotamia is an area where there are practically no trees suitable for processing (remember the Slavic ones or the Egyptian papyrus, made from a bamboo stem), and there was no stone there. But there was plenty of clay in the river floods, so it was widely used by the Sumerians.

The writing blank was a clay cake, it had the shape of a circle or a rectangle. The marks were made with a special stick called a kapama. It was made of hard material, such as bone. The tip of the kapama was triangular. The writing process involved dipping a stick into soft clay and leaving a specific design. When the kapama was pulled out of the clay, the elongated part of the triangle left a wedge-like mark, hence the name “cuneiform”. To preserve what was written, the tablet was fired in a kiln.

The origins of syllabics

As stated above, before cuneiform appeared, the Sumerians had another type of writing - pictography, then ideography. Later, the signs became simplified, for example, instead of a whole bird, only a paw was depicted. And the number of signs used is gradually decreasing - they become more universal, they begin to mean not only direct concepts, but also abstract ones - for this it is enough to depict another ideogram next to it. Thus, “another country” and “woman” standing next to each other meant the concept of “slave”. Thus, the meaning of specific signs became clear from the general context. This way of expression is called logography.

Still, it was difficult to depict ideograms on clay, so over time, each of them was replaced by a certain combination of dashes-wedges. This pushed the writing process further by allowing syllables to match specific sounds. Thus, syllabic writing began to develop, which lasted for quite a long time.

Decoding and meaning for other languages

The mid-19th century was marked by attempts to understand the essence of the Sumerian cuneiform writing. Grotefend made great strides in this. However, what was found made it possible to finally decipher many texts. The rock-cut texts contained examples of ancient Persian, Elamite and Akkadian script. Rawlins was able to decipher the texts.

The emergence of Sumerian cuneiform influenced the writing of other countries of Mesopotamia. As civilization spread, it brought with it the verbal-syllabic type of writing, which was adopted by other peoples. The entry of Sumerian cuneiform into Elamite, Hurrian, Hittite and Urartian writing is especially clear.

Type: syllabic-ideographic

Language family: not installed

Localization: Northern Mesopotamia

Propagation time:3300 BC e. - 100 AD e.

The Sumerians called the homeland of all mankind the island of Dilmui, identified with modern Bahrain in the Persian Gulf.

The earliest is represented by texts found in the Sumerian cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, dated 3300 BC.

The Sumerian language still continues to remain a mystery to us, since even now it has not been possible to establish its relationship with any of the known language families. Archaeological materials suggest that the Sumerians created the Ubaid culture in the south of Mesopotamia at the end of the 5th - beginning of the 4th millennium BC. e. Thanks to the emergence of hieroglyphic writing, the Sumerians left many monuments of their culture, imprinting them on clay tablets.

The cuneiform script itself was a syllabic script, consisting of several hundred characters, of which about 300 were the most common; these included more than 50 ideograms, about 100 signs for simple syllables and 130 for complex ones; there were signs for numbers in the hexadecimal and decimal systems.

Sumerian writing developed over 2200 years

Most signs have two or several readings (polyphonism), since often, next to Sumerian, they also acquired a Semitic meaning. Sometimes they depicted related concepts (for example, “sun” - bar and “shine” - lah).

The invention of Sumerian writing itself was undoubtedly one of the largest and most significant achievements of the Sumerian civilization. Sumerian writing, which went from hieroglyphic, figurative signs-symbols to the signs that began to write the simplest syllables, turned out to be an extremely progressive system. It was borrowed and used by many peoples who spoke other languages.

At the turn of the IV-III millennium BC. e. we have indisputable evidence that the population of Lower Mesopotamia was Sumerian. The widely known story of the Great Flood first appears in Sumerian historical and mythological texts.

Although Sumerian writing was invented exclusively for economic needs, the first written literary monuments appeared among the Sumerians very early: among records dating back to the 26th century. BC e., there are already examples of folk wisdom genres, cult texts and hymns.

Due to this circumstance, the cultural influence of the Sumerians in the Ancient Near East was enormous and outlived their own civilization for many centuries.

Subsequently, writing loses its pictorial character and transforms into cuneiform.

Cuneiform writing was used in Mesopotamia for almost three thousand years. However, later it was forgotten. For tens of centuries, cuneiform kept its secret, until in 1835 the unusually energetic Englishman Henry Rawlinson, an English officer and lover of antiquities, deciphered it. One day he was informed that an inscription had been preserved on a steep cliff in Behistun (near the city of Hamadan in Iran). It turned out to be the same inscription, written in three ancient languages, including ancient Persian. Rawlinson first read the inscription in this language known to him, and then managed to understand the other inscription, identifying and deciphering more than 200 cuneiform characters.

In mathematics, the Sumerians knew how to count in tens. But the numbers 12 (a dozen) and 60 (five dozen) were especially revered. We still use the Sumerian heritage when we divide an hour into 60 minutes, a minute into 60 seconds, a year into 12 months, and a circle into 360 degrees.

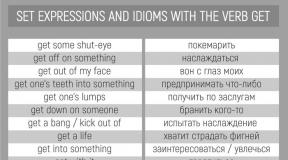

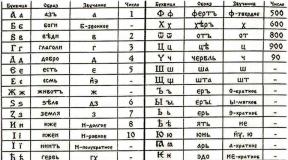

In the figure you see how over 500 years hieroglyphic images of numerals turned into cuneiform ones.

Modification of Sumerian numerals from hieroglyphs to cuneiform

Sumerian cuneiform

Sumerian writing, which is known to scientists from surviving cuneiform texts of the 29th–1st centuries BC. e., despite active study, still largely remains a mystery. The fact is that the Sumerian language is not similar to any of the known languages, so it was not possible to establish its relationship with any language group.

Initially, the Sumerians kept records using hieroglyphs - drawings that denoted specific phenomena and concepts. Subsequently, the sign system of the Sumerian alphabet was improved, which led to the formation of cuneiform in the 3rd millennium BC. e. This is due to the fact that records were kept on clay tablets: for ease of writing, hieroglyphic symbols were gradually transformed into a system of wedge-shaped strokes applied in different directions and in various combinations. One cuneiform symbol represented a word or syllable. The writing system developed by the Sumerians was adopted by the Akkadians, Elamites, Hittites and some other peoples. That is why Sumerian writing survived much longer than the Sumerian civilization itself existed.

According to research, a unified writing system in the states of Lower Mesopotamia was used already in the 4th–3rd millennia BC. e. Archaeologists have managed to find many cuneiform texts. These are myths, legends, ritual songs and hymns of praise, fables, sayings, debates, dialogues and edifications. Initially, the Sumerians created writing for economic needs, but soon fiction began to appear. The earliest cult and artistic texts date back to the 26th century BC. e. Thanks to the works of Sumerian authors, the genre of tale-argument developed and spread, which became popular in the literature of many peoples of the Ancient East.

It is believed that Sumerian writing spread from one place, which at that time was an authoritative cultural center. Many data obtained in the course of scientific work suggest that this center could be the city of Nippur, in which there was a school for scribes.

Archaeological excavations of the ruins of Nippur first began in 1889. Many valuable finds were made during excavations that took place shortly after the Second World War. As a result, the ruins of three temples and a large cuneiform library with texts on a variety of issues were discovered. Among them was the so-called “school canon of Nippur” - a work intended for study by scribes. It included tales about the exploits of the great heroes-demigods Enmesharra, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh, as well as other literary works.

Sumerian cuneiform: above - stone tablet from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal; at the bottom - fragment of a diorite stele on which the code of laws of the Babylonian king Hammurabi is written

Extensive cuneiform libraries were found by archaeologists in the ruins of many other cities of Mesopotamia - Akkad, Lagash, Nineveh, etc.

One of the important monuments of Sumerian writing is the “Royal List”, found during the excavations of Nippur. Thanks to this document, the names of the Sumerian rulers have reached us, the first of whom were the heroic demigods Enmesharr, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh, and legends about their deeds.

Legends tell of a dispute between Enmesharr and the ruler of the city of Aratta, located far in the East. Legend connects the invention of writing with this dispute. The fact is that the kings took turns asking each other riddles. No one was able to remember one of Enmesharr's ingenious riddles, which is why the need arose for a method of transmitting information other than oral speech.

The key to deciphering cuneiform texts was found completely independently of each other by two amateur researchers G. Grotenfend and D. Smith. In 1802, Grotenfend, analyzing copies of cuneiform texts found in the ruins of Persepolis, noticed that all cuneiform signs have two main directions: from top to bottom and from left to right. He came to the conclusion that texts should not be read vertically, but horizontally, from left to right.

Since the texts he studied were funerary inscriptions, the researcher suggested that they could begin in much the same way as later inscriptions in Persian: “So-and-so, the great king, the king of kings, the king of such and such places, the son of the great king ... “As a result of analyzing the available texts, the scientist came to the conclusion that the inscriptions distinguish between those groups of signs that should, according to his theory, convey the names of the kings.

In addition, there were only two options for the first two groups of symbols that could mean names, and in some texts Grotenfend found both options.

Further, the researcher noticed that in some places the initial formula of the text does not fit into its hypothetical scheme, namely, in one place there is no word denoting the concept of “king”. The study of the arrangement of signs in the texts made it possible to make the assumption that the inscriptions belong to two kings, father and son, and the grandfather was not a king. Since Grotenfend knew that the inscriptions referred to Persian kings (according to the archaeological research during which these texts were discovered), he concluded that they were most likely talking about Darius and Xerxes. By correlating the Persian spelling of names with the cuneiform, Grotenfend was able to decipher the inscriptions.

No less interesting is the history of the study of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In 1872, an employee of the British Museum, D. Smith, was deciphering cuneiform tablets found during the excavations of Nineveh. Among the tales about the exploits of the hero Gilgamesh, who was two-thirds a deity and only one-third a mortal man, the scientist was especially interested in a fragment of the legend of the Great Flood:

This is what Utnapishtim says to the hero, who survived the flood and received immortality from the gods. However, later in the story there began to be gaps, a piece of text was clearly missing.

In 1873, D. Smith went to Kuyundzhik, where the ruins of Nineveh had previously been discovered. There he was lucky enough to find the missing cuneiform tablets.

After studying them, the researcher came to the conclusion that Utnapishtim is none other than the biblical Noah.

The story of the ark, or ship, which Utnapishtim ordered on the advice of the god Ea, the description of a terrible natural disaster that struck the earth and destroyed all life except those who boarded the ship, surprisingly coincides with the biblical story of the Great Flood. Even the dove and raven, which Utnapishtim releases after the end of the rain to find out whether the waters have subsided or not, are also in the biblical legend. According to the Epic of Gilgamesh, the god Enlil made Utnapishtim and his wife like gods, that is, immortal. They live across the river that separates the human world from the other world:

Hitherto Utnapishtim was a man,

From now on, Utnapishtim and his wife are like us, gods;

Let Utnapishtim live at the mouths of rivers, in the distance!

Gilgamesh, or Bilga-mes, whose name is often translated as “ancestor-hero,” the hero of the Sumerian epic, was considered the son of the hero Lugalbanda, the high priest of Kulaba, ruler of the city of Uruk, and the goddess Ninsun.

According to the “Royal List” from Nippur, Gilgamesh ruled Uruk for 126 years in the 27th–26th centuries BC. e.

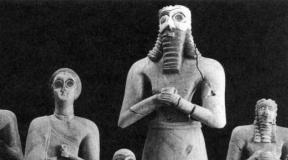

Gilgamesh with a lion. VIII century BC e.

Gilgamesh was the fifth king of the first dynasty, to which his father Lugalbanda and Dumuzi, the husband of the goddess of love and war Inanna, belonged. For the Sumerians, Gilgamesh is not just a king, but a demigod possessing superhuman qualities, therefore his deeds and the duration of his life significantly exceed the corresponding characteristics of the subsequent rulers of Uruk.

The name of Gilgamesh and the name of his son Ur-Nungal were found in the list of rulers who took part in the construction of the general Sumerian temple of Tummal in Nippur. The construction of a fortress wall around Uruk is also associated with the activities of this legendary ruler.

There are several ancient tales about the exploits of Gilgamesh. The tale “Gilgamesh and Agga” tells about real events of the late 27th century BC. e., when the warriors of Uruk defeated the troops of the city of Kish.

The tale “Gilgamesh and the Mountain of the Immortal” tells of a trip to the mountains where warriors led by Gilgamesh defeat the monster Humbaba. The texts of two tales – “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven” and “The Death of Gilgamesh” – are poorly preserved.

Also, the legend “Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Underworld” has reached us, which reflects the ideas of the ancient Sumerians about the structure of the world.

According to this legend, in the garden of the goddess Inanna there grew a magical tree, from the wood of which the goddess intended to make herself a throne. But the Anzud bird, a monster that caused thunderstorms, and the demon Lilith settled on the tree, and a snake settled under the roots. At the request of the goddess Inanna, Gilgamesh defeated them, and from wood he made for the goddess a throne, a bed and magical musical instruments, to the sounds of which the young men of Uruk danced. But the women of Uruk became indignant at the noise, and the musical instruments fell into the realm of the dead. The servant of the ruler of Uruk, Enkidu, went to get musical instruments, but failed to return back. However, at the request of Gilgamesh, the gods allowed the king to talk with Enkidu, who told him about the laws of the kingdom of the dead.

Tales of the deeds of Gilgamesh became the basis of the Akkadian epic, cuneiform records of which were discovered during excavations of Nineveh in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, dated to the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. e. There are also several different versions, records of which were found during excavations in Babylon and in the ruins of the Hittite kingdom.

The text that was discovered in Nineveh, according to legend, was written down from the words of the Uruk spellcaster Sinlique-uninni. The legend is recorded on 12 clay tablets. Separate fragments of this epic were found in Ashur, Uruk and Sultan Tepe.

The audacity and strength of the king of Uruk forced the inhabitants of the city to turn to the gods for protection from his tyranny. Then the gods created the strongman Enkidu from clay, who entered into single combat with Gilgamesh. However, the heroes became not enemies, but friends. They decided to take a hike into the mountains for cedars. The monster Humbaba lived in the mountains, which they defeated.

The story goes on to tell how the goddess Inanna offered her love to Gilgamesh, but he rejected her, reproaching her for being unfaithful to her former lovers. Then, at the request of the goddess, the gods send a gigantic bull that seeks to destroy Uruk. Gilgamesh and Enkidu defeat this monster, but Inanna's anger causes the death of Enkidu, who suddenly loses his strength and dies.

Gilgamesh grieves for his dead friend. He cannot come to terms with the fact that death awaits him, so he goes in search of a herb that gives immortality. Gilgamesh's journeys are similar to the journeys of many other legendary heroes to another world. Gilgamesh passes the desert, crosses the “waters of death” and meets the wise Utnapishtim, who survived the flood. He tells the hero where you can find the herb of immortality - it grows at the bottom of the sea. The hero manages to get it, but on the way home he stops at a spring and falls asleep, and at this time a snake swallows the grass - so the snakes change their skin, thereby renewing their lives. Gilgamesh has to give up his dream of physical immortality, but he believes that the glory of his deeds will live in the memory of people.

It is interesting to note that the ancient Sumerian storytellers were able to show how the character of the hero and his worldview were changing. If at first Gilgamesh demonstrates his strength, believing that no one can resist him, then as the plot develops, the hero realizes that human life is short and fleeting. He thinks about life and death, experiences grief and despair. Gilgamesh is not used to submitting even to the will of the gods, so the thought of the inevitability of his own end causes him to protest.

The hero does everything possible and impossible to break out of the tight confines of fate. The tests he has passed make him understand that this is possible for a person only thanks to his deeds, the glory of which lives in legends and traditions.

Another written monument made in cuneiform is the code of laws of the Babylonian king Hammurabi, dated approximately 1760 BC. e. A stone slab with the text of laws carved on it was found by archaeologists at the beginning of the 20th century during excavations in the city of Susa. Many copies of the Code of Hammurabi were also found during excavations of other Mesopotamian cities, such as Nineveh. The Code of Hammurabi is distinguished by a high degree of legal elaboration of concepts and the severity of punishments for various crimes. The laws of Hammurabi had a huge influence on the development of law in general and on the codes of laws of different peoples in later eras.

However, the Code of Hammurabi was not the first collection of Sumerian laws. In 1947, archaeologist F. Style, during excavations of Nippur, discovered fragments of the legislative code of King Lipit-Ishtar, dated to the 20th century BC. e. Law codes existed at Ur, Isin and Eshnunna: they were probably taken as a basis by the developers of the Code of Hammurabi.

From the book When Cuneiform Spoke author Matveev Konstantin PetrovichChapter III When cuneiform began to speak Created several millennia BC, cuneiform was an outstanding phenomenon in the cultural life of mankind, in the history of human civilization. Thanks to cuneiform writing, people were able to record their achievements in various

authorPart 1. Sumerian civilization

From the book Ancient Sumer. Essays on culture author Emelyanov Vladimir VladimirovichPart 2. Sumerian culture

From the book History of the Ancient World. Volume 1. Early antiquity [various. auto edited by THEM. Dyakonova] author Sventsitskaya Irina SergeevnaLecture 5: Sumerian and Akkadian culture. Religious worldview and art of the population of lower Mesopotamia of the 3rd millennium BC. Emotionally colored comparison of phenomena according to the principle of metaphor, i.e. by combining and conditionally identifying two or more

From the book Sumerians. The Forgotten World [edited] author Belitsky MarianThe Sumerian parable about “Job” The story of how severe suffering befell a certain man - his name is not given - who was distinguished by his health and was rich, begins with a call to praise God and offer prayer to him. After this prologue, a nameless man appears

From the book History of the Ancient East author Lyapustin Boris Sergeevich“The Sumerian mystery” and the Nippurian union With the settlement at the beginning of the 4th millennium BC. e. On the territory of Lower Mesopotamia, the Sumerian aliens, the archaeological culture of Ubeid was replaced here by the Uruk culture. Judging by the later memories of the Sumerians, the original center of their settlement

From the book History of World Civilizations author Fortunatov Vladimir Valentinovich§ 3. Sumerian civilization One of the oldest civilizations, along with the ancient Egyptian one, is the Sumerian civilization. It originated in Western Asia, in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This area was called Mesopotamia in Greek (which in Russian sounds like “interfluve”). IN

From the book Sumerians. Forgotten World author Belitsky Marian From the book History of Weddings author Ivik OlegMarriage cuneiform For some, marriages take place in heaven, for others - on sinful earth. For the inhabitants of ancient Mesopotamia, marriages took place mainly in the bowels of the bureaucratic machine. On the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, they generally loved accounting and control. All events: and past,

From the book Ancient East author Nemirovsky Alexander ArkadevichThe Sumerian riddle One of the traditional riddles of oriental studies is the question of the ancestral homeland of the Sumerians. It remains unresolved to this day, since the Sumerian language has not yet been reliably associated with any of the currently known language groups, although there are no candidates for such a relationship

From the book Curses of Ancient Civilizations. What's coming true, what's about to happen author Bardina Elena From the book 50 Great Dates in World History author Schuler JulesCuneiform Unlike Egypt, where nearby mountains allow stone to be mined in abundance, stone was used little in Mesopotamia (only a few statues and steles survive). Royal palaces and ziggurat temples in the form of multi-story towers were built from dried clay,

Cuneiform - writing, the signs of which consist of combinations of wedge-shaped dashes. Such signs were squeezed out on damp clay. Cuneiform was used by ancient peoples Western Asia, it arose at the beginning of the third millennium BC. V Sumer(Southern Mesopotamia), was later adapted for Akkadian, Elamite, Hittite, Urartian languages. By origin, cuneiform was an ideographic-rebus writing, later transformed into a verbal-syllabic writing.

Cuneiform

Development of cuneiform

Development of cuneiform characters

Cuneiform originated from pictorial writing, the signs of which were drawings of animals, objects and people and conveyed concepts. As the need arose to write down more complex texts, signs began to be used in their sound meaning and grammatical indicators of gender, case, person, and number began to be noted in writing. As the writing system became more complex, the shape of the characters became simpler, and the drawings turned into combinations of straight and slashes. It was the use of cuneiform signs in their sound meaning that made it possible to adapt cuneiform to convey other languages.

Initially, the Sumerians conveyed with images the names of individual specific objects and general concepts. Thus, the drawing of the leg began to convey the concepts of “walking” (Sumerian du-, ra-), “standing” (gub-), “bringing” (tum-). There were about a thousand ideographic signs in total. They were notes that consolidated the main points of the conveyed thought, rather than coherent speech. Since the signs were associated with specific words, this made it possible to use them to denote sound combinations regardless of meaning. The foot sign could no longer be used only to convey verbs of motion, but also for syllables. Verbal-syllabic writing developed into a system by the middle of the third millennium BC. The base of a noun or verb was expressed by an ideogram (a sign for a concept), and grammatical indicators and function words were expressed by signs in a syllabic meaning. Equally sounded stems with different meanings were expressed by different signs (homophony). Each sign could have several meanings, both syllabic and related to concepts (polyphony). To highlight words that expressed the concepts of a number of specific categories (for example, birds, fish, profession), a small number of determiners were used - unpronounceable indicators. The number of characters was reduced to 600, not counting combined ones.

As writing accelerated, the drawings became simpler. The lines of the characters were pressed in with a rectangular reed stick, which entered the clay at an angle and therefore created a wedge-shaped depression. Direction of writing: first in vertical columns from right to left, later - line by line, from left to right. The forms of cuneiform monuments are varied: prisms, cylinders, cones, stone slabs; The most common tiles are made from dried clay. Archaeologists have discovered a large number of cuneiform texts: business documents, historical inscriptions, epics, dictionaries, mathematical works, scientific works, religious and magical records.

Akkadians(Babylonians and Assyrians) adapted cuneiform for their Semitic inflectional language in the mid-third millennium BC, reducing the number of characters to three hundred and creating new syllabic values corresponding to the Akkadian phonetic system. At the same time, purely phonetic (syllabic) recordings of words began to be used, but Sumerian ideograms and the spelling of individual words and expressions (in Akkadian reading) also continued to be used. The Akkadian cuneiform system spread beyond Mesopotamia, also adapting to the Elamite, Hurrian, Hittite-Luwian, and Urartian languages. Starting from the second half of the first millennium BC. Cuneiform was used for religious and legal purposes only in certain cities of the Southern Mesopotamia for the already dead Sumerian and Akkadian languages. The last cuneiform document in Akkadian dates back to 75 BC.

Ugaritic cuneiform alphabet from the city Ugarit(Ras Shamra) second millennium BC. became an adaptation of the ancient Semitic alphabet to writing on clay; it is similar to Akkadian cuneiform only in the way of marking. In the 6th-4th centuries BC. Old Persian syllabic cuneiform became widespread. Its deciphering was started by the German schoolteacher Georg Grotefend, who in 1802 managed to read the Behistun inscription of the Persian king Darius I. The presence of trilingual Persian-Elamite-Akkadian inscriptions allowed the British diplomat Henry Rawlinson to begin deciphering the Akkadian texts in 1851. This work was later continued by the British scientist E. Hinks and the French scientist J. Oppert. In 1869, Jules Oppert suggested that the Sumerians were the inventors of cuneiform writing. The Sumerian cuneiform itself was deciphered in the late 19th - early 20th centuries, the Ugaritic one - in 1930-1932 by the French scientist C. Virollo and the German scientist H. Bauer.

Read also...

- Plato - biography and philosophical teachings What Plato believed

- Common ancestors of humans and apes

- Electronic formula nb. Electronic formulas. Distribution of electrons using the periodic system of D. I. Mendeleev

- Endangered languages. What is a dead language? List of dead languages. Should we start sounding the alarm?