Philosophy of Plato. Elements of teaching. Plato's philosophy The concept of eidos was developed by the ancient philosopher

Plato's teaching about the idea and its meaning

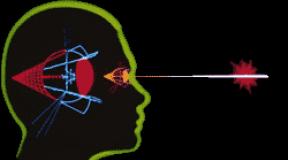

He solves the main question of philosophy unambiguously - idealistically. The material world that surrounds us and which we perceive with our senses is, according to Plato, only a “shadow” and is derived from the world of ideas, i.e. the material world is secondary. All phenomena and objects of the material world are transitory, arise, perish and change (and therefore cannot be truly existing), ideas are unchanging, motionless and eternal. For these properties, Plato recognizes them as genuine, valid being and elevates them to the rank of the only object of truly true knowledge.

The possibility of the emergence of this form of idealism, as V.I. Lenin spoke about it in his “Philosophical Notebooks,” lies already in the first elementary abstraction (“house” in general along with individual houses). Plato explains, for example, the similarity of all tables existing in the material world by the presence of the idea of a table in the world of ideas. All existing tables are just a shadow, a reflection of the eternal and unchanging idea of a table. This, as V.I. Lenin said, is a reversal of reality. In fact, the idea of a table arises as an abstraction, as an expression of a certain similarity (that is, abstraction from the differences) of many individual, concrete tables. Plato separates the idea from real objects (individuals), absolutizes it and proclaims it a priori in relation to them. Ideas are genuine entities, they exist outside the material world and do not depend on it, they are objective (hypostasis of concepts), the material world is only subordinate to them. This is the core of Plato's objective idealism (and rational objective idealism in general).

Between the world of ideas, as genuine, real being, and non-existence (i.e., matter as such, matter in itself), according to Plato, there exists apparent being, derivative being (i.e., the world of truly real, sensually perceived phenomena and things) , which separates true being from non-existence. Real, real things are a combination of an a priori idea (true being) with passive, formless “receiving” matter (non-existence).

The relationship between ideas (being) and real things (apparent being) is an important part of Plato's philosophical teaching. Sensibly perceived objects are nothing more than a likeness, a shadow, in which certain patterns - ideas are reflected. In Plato one can also find a statement of the opposite nature. He says that ideas are present in things. This relationship of ideas and things, if interpreted according to the views of Plato of the last period, opens up a certain possibility of movement towards irrationalism.

Plato pays a lot of attention, in particular, to the issue of “hierarchization of ideas.” This hierarchization represents a certain ordered system of objective idealism. Above all, according to Plato, is the idea of beauty and goodness. It not only surpasses all really existing goodness and beauty in that it is perfect, eternal and unchangeable (just like other ideas), but also stands above other ideas. Cognition, or achievement, of this idea is the pinnacle of real knowledge and evidence of the fullness of life. Plato's teaching about ideas was developed in most detail in the main works of the second period - "Symposium", "Law", "Phaedo" and "Phaedrus".

Plato on the goal and stages of knowledge

Plato on purpose. All things in the world are subject to change and development. This is especially true for the living world. Developing, everything strives towards the goal of its development. Hence, another aspect of the concept of “idea” is the goal of development, an idea as an ideal. A person also strives for some kind of ideal, for perfection. For example, when he wants to create a sculpture out of stone, he already has in his mind the idea of a future sculpture, and the sculpture arises as a combination of material, i.e. stone, and an idea existing in the mind of the sculptor. Real sculpture does not correspond to this ideal, because in addition to the idea, it is also involved in matter.

Matter is nothingness. Matter is non-existence and the source of everything bad, and in particular evil. And the idea, as I have already said, is the true existence of a thing.

A given thing exists because it is involved in an idea. In the world, everything unfolds according to some goal, and a goal can only have that which has a soul. Stages of knowledge: opinion and science.

1. Beliefs and opinions (doxa)

2. Insight-understanding-faith (pistis). The beginning of the transformation of the spirit.

3. Pure wisdom (noesis). Comprehension of the truth of Being. The concept of anamnesis (the recollection by the soul in this world of what it saw in the world of ideas) explains the source, or the possibility of knowledge, the guarantee of which is the original intuition of truth in our soul. Plato defines stages and specific ways of knowing in the Republic and dialectical dialogues.

In the Republic, Plato starts from the position that knowledge is proportional to being, so that only what exists in the maximum way is knowable in the most perfect way; it is clear that non-existence is absolutely unknowable. But, since there is an intermediate reality between being and non-being, that is, the sphere of the sensible, a mixture of being and non-being (therefore it is the object of becoming), there is also an intermediate knowledge between science and ignorance: and this intermediate form of knowledge is “doxa”, "doxa", opinion.

Opinion, according to Plato, is almost always deceptive. Sometimes, however, it can be both plausible and useful, but it never has a guarantee of its own accuracy, remaining unstable, just as the world of feelings in which opinion is found is fundamentally unstable. To impart stability to it, it is necessary, Plato asserts in the Meno, to have a “causal basis,” which allows one to fix an opinion through the knowledge of causes (i.e., ideas), and then the opinion turns into science, or “episteme.”

Plato specifies both opinion (doxa) and science (episteme); opinion is divided into simple imagination (eikasia) and belief (pistis); science is a kind of mediation (dianoia) and pure wisdom (noesis). Each of the stages and forms of knowledge correlates with a form of being and reality. Corresponding to the two stages of the sensory are eikasia and pistis, the first - shadows and images of things, the second - the things themselves; dianoia and noesis are two stages of the intelligible, the first is mathematical and geometric knowledge, the second is pure dialectics of ideas. Mathematical-geometric knowledge is a medium because it uses visual elements (figures, for example) and hypotheses, “noesis” is the highest and absolute principle on which everything depends, and this is pure contemplation that holds Ideas, the harmonious conclusion of which is the Idea of the Good. Myth about the Cave and the doctrine of manThe Myth of the CaveIn the center of the "State" we find the famous myth about the Cave. Little by little, this myth turned into a symbol of metaphysics, epistemology and dialectics, as well as ethics and mysticism: a myth that expresses the whole of Plato. This is where we will finish our analysis.

Let's imagine people who live underground, in a cave with an entrance directed towards the light, which illuminates the entire length of one of the walls of the entrance. Let us also imagine that the inhabitants of the cave are also tied at the feet and hands, and being motionless, they turn their gaze deeper into the cave. Let us also imagine that right at the very entrance to the cave there is a shaft of stones as tall as a man, on the other side of which people move, carrying statues of stone and wood and all kinds of images on their shoulders. To top it all off, you need to see a huge fire behind these people, and even higher - a shining sun. Outside the cave, life is in full swing, people are saying something, and their talk echoes in the belly of the cave.

Thus, the prisoners of the cave are unable to see anything except the shadows cast by the figurines on the walls of their gloomy abode; they hear only the echo of someone’s voices. However, they believe that these shadows are the only reality, and without knowing, seeing or hearing anything else, they take echoes and shadow projections at face value. Now suppose that one of the prisoners decides to throw off his shackles, and after considerable effort he becomes accustomed to a new vision of things, say, seeing the figurines moving outside, he would understand that they are real, and not the shadows he had previously seen. Finally, suppose that someone dared to bring the prisoner to freedom. And after the first minute of blinding from the rays of the sun and the fire, our prisoner would see things as such, and then the sun's rays, first reflected, and then their pure light in itself; then, having understood what true reality is, he would understand that the sun is the true cause of all visible things. So what does this myth symbolize?

Four Meanings of the Cave Myth

1. this is an idea of the ontological gradation of being, of the types of reality - sensual and supersensible - and their subtypes: shadows on the walls are the simple appearance of things; statues are sensually perceived things; a stone wall is a demarcation line separating two kinds of existence; objects and people outside the cave are true existence leading to ideas; Well, the sun is the Idea of Good.

2. myth symbolizes the stages of knowledge: contemplation of shadows - imagination (eikasia), vision of statues - (pistis), i.e. beliefs, from which we move on to the understanding of objects as such and to the image of the sun, first indirectly, then directly - this phases of dialectics with various stages, the last of which is pure contemplation, intuitive intelligibility.

3. We also have aspects: ascetic, mystical and theological. Life under the sign of feelings and only feelings is a cave life. Life in the spirit is life in the pure light of truth. The path of ascent from the sensual to the intelligible is “liberation from shackles,” that is, transformation; finally, the highest knowledge of the sun-Good is the contemplation of the divine.

4. This myth also has a political aspect with a truly Platonic sophistication. Plato speaks of the possible return to the cave of someone who has once been freed. To return with the goal of liberating and leading to freedom those with whom he spent many years of slavery.

EIDOS (Greek εἶδος, Latin forma, etymological identity with the Russian “view”) is a term of ancient Greek philosophy. In pre-philosophical word usage (starting with Homer) and for the most part among the Pre-Socratics - (external) “appearance”, “image”, but already in the 5th century. BC. (in Herodotus 1, 94 and Thucydides 2, 50) a meaning close to “species” as a classification unit is attested. In Democritus (B 167 = No. 288 Lu.) - one of the designations of “atom”, actually “(geometric) form”, “figure”.

Eidos (Kirilenko)

EIDOS (Greek eidos - appearance, image, essence) is a concept of ancient philosophy, meaning “concrete appearance”, “bodily, plastic appearance in thinking”. In the Platonic tradition, eidos is an image-idea, an ideal essence in its concrete manifestation, a plastically completed object of intellectual contemplation. In the philosophy of the 20th century, it is used in the sense of the highest mental abstraction, which, nevertheless, is given visually, concretely and completely independently. For example, “ideal form” or “pure essence” in the teachings of E. Husserl.

Eidos (Gritsanov)

EIDOS (Greek eidos - appearance, image, sample) is a term of ancient philosophy that captures the method of organizing an object, as well as the categorical structure of medieval and modern philosophy, interpreting the original semantics of a given concept, respectively, in traditional and non-traditional contexts. In ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of E. was used to designate external structure: appearance as appearance (Milesian school, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, atomists). The correlation of E. with the substrate arche is the fundamental semantic opposition of ancient philosophy, and the acquisition of E. by a thing.

in ancient philosophy (especially in Plato) and further - ideas, primary non-material prototypes of things, their spiritual meanings. The world of eidos (ideas) is a special world of primary essences - the basis of being according to Plato. Plato's doctrine of ideas is the most important part of Platonic philosophy and philosophical Platonism, the forerunner of philosophical idealism.

Excellent definition

Incomplete definition ↓

EIDOS

Greek eidos - appearance, image, sample) is a term of ancient philosophy that captures the method of organizing an object, as well as the categorical structure of medieval and modern philosophy, interpreting the original semantics of a given concept - respectively - in traditional and non-traditional contexts. In ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of E. was used to designate external structure: appearance as appearance (Milesian school, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, atomists). The correlation of element with the substrate arche acts as a fundamental semantic opposition to ancient philosophy, and the acquisition of element by a thing is actually thought of as its formation, which sets the close semantic connection of the concept of element with the concept of form (see Hylemorphism). The fundamental initial design of the structural units of the universe is fixed by Democritus by designating the atom with the term “E.”. The eidotic design of a thing is conceived in pre-Socratic natural philosophy as a result of the influence on the passive substantial principle of the active principle, embodying the pattern of the world and associated with mentality and goal-setting as carrying within itself the image (E.) of the future thing (logos, Nus, etc.). In Greek philosophy, language and culture as a whole, in this regard, the concept of E. turns out to be virtually equivalent, from the point of view of semantics, to the concept of idea (Greek idea - appearance, image, appearance, kind, method). And if the phenomenon of the substrate is associated in ancient culture with the material (respectively, the maternal) principle, then the source of E. is associated with the paternal, male principle - see Idealism). If, within the framework of pre-Socratic philosophy, E. was understood as the external structure of an object, then in Plato the content of the concept “E.” is significantly transformed: first of all, E. is understood not as an external, but as an internal form, i.e. immanent way of being of an object; In addition, E. acquires an ontologically independent status in Plato’s philosophy: the transcendental world of ideas or, synonymously, the world of E. as a set of absolute and perfect examples of possible things. The perfection of E. (= ideas) is denoted by Plato through the semantic figure of the immobility of its essence (oysia), initially equal to itself (compare with the Genesis of the Eleatics, whose self-sufficiency was recorded as immobility). E.'s way of being, however, is his incarnation and embodiment in multiple objects, structured in accordance with his gestalt (E. as a model) and therefore bearing in their structure and form (E. as a type) his image (E. as an image) . In this context, the interaction between object and subject in the process of cognition is interpreted by Plato as communication (koinonia) between E. object and the soul of the subject, the result of which is the imprint of E. to the soul of a person, i.e. noema (noema) as a conscious E., - subjective E. of objective E. (Parmenides, 130-132c). In Aristotle's philosophy, E. is thought of as immanent to the material substrate of an object and inseparable from the latter (in the 19th century, this emphasis of Aristotle's attitude was called hyleomorphism: Greek hile - matter, morphe - form). Any transformation of an object is interpreted by Aristotle as a transition from the deprivation of one or another element (accidental non-existence) to its acquisition (accidental formation). In Aristotle's taxonomy (in the field of logic and biology), the term "E." is also used in the meaning of “species” as a classification unit (“species” as a set of objects of a certain “species” as a method of organization) - in relation to the “genus” (genos). In a similar meaning, the term "E." also used in the tradition of ancient history (Herodotus, Thucydides). Stoicism brings the concept of energy closer to the concept of logos, emphasizing in it the creative, organizing principle (“spermatic logos”). Within the framework of Neoplatonism, E. in the original Platonic sense is attributed to the One as his “thoughts” (Albinus), Nous as the Demiurge (Plotinus), and numerous E. in the Aristotelian sense (as immanent gestalts of the object organization) - to products of emanation. The semantics of E. as the archetypal basis of things is updated in medieval philosophy: archetipium as a prototype of things in the thinking of God in orthodox scholasticism (see Anselm of Canterbury on the original pre-existence of things as archetypes in God’s conversation with himself, similar to the pre-existence of a work of art in the mind of the master) ; John Duns Scotus about haecceitos (thisness) as a prior thing of her selfhood, actualized in the free creative will of God) and in unorthodox directions of scholastic thought: the concept of species (the image is the Latin equivalent of E.) in late Scotism; presumption of visiones (mental images in Nicholas of Cusa and others. In late classical and non-classical philosophy, the concept of E. finds a second wind: speculative forms of unfolding the content of the Absolute Idea before its objectification in the otherness of nature in Hegel; Schopenhauer’s teaching about the “world of reasonable ideas”; eidology Husserl, where species is thought of as an intellectual, but at the same time concretely given abstraction as a subject of “intellectual intuition”, the concept of “ideas” by E.I. Gaiser in neo-Thomism, etc. In modern psychology, the term “eidetism” denotes the characteristic of the phenomenon of memory associated with extremely vivid clarity of the recorded object, within which the representation is practically not inferior to direct perception according to the criteria of meaningful detail and emotional and sensory richness.

Excellent definition

Incomplete definition ↓

Plato is the founder of objective idealism in philosophy and the European style of thinking in general. The main achievement of Plato's philosophy is considered to be the doctrine of eidos, ideas. This doctrine contains the following main provisions:

1. The sensory world of things cannot be true being (reality), because it constantly becomes (changes) and is never what it was a moment ago. And if he is always not what he was before, and every moment he no longer becomes what he is now, then he is not this, and not this, and not another, and has no definition at all, because he never may be equal (identical) to itself. True being can only be something unchangeable and equal (identical) to itself, about which we can always say with certainty that it is what it is now, has always been and will always be.

2. The world of sensory things is not a true reality also because any thing is in physical space, consists of parts, can decompose into them, and is therefore doomed to change and death. And what will die sooner or later no longer exists now in the meaning of all this, and, therefore, despite the fact that it physically exists, it is not genuine, since in the final fact it no longer exists.

3. The world of sensory things cannot be a true reality also because it is plural, and true reality can only be singular, since only the individual does not change and, as unchangeable, is therefore always identical to itself and eternal.

4. In the world of sensory things, therefore, there is nothing of true reality, but since this world truly exists, it takes this authenticity, is saturated with this authenticity from somewhere outside itself, from some true reality, eternal, unchanging and singular .

5. Thus, there is a certain genuine reality, which is the determining principle in relation to the material world and endows it with authenticity from itself, that is, makes the world a reality. But this true reality is not this world itself, or something similar in characteristics to this world. For, in order to be authentic, it must be an immaterial, incorporeal phenomenon, located outside of physical space, not decompose into parts, not disintegrate, and, thus, be immortal and indestructible, which alone is authenticity.

6. Immaterial true being, which is the source of the reality of material things, must be, as said above, single, but the world of things and phenomena is multiple. It goes without saying that something singular can determine the presence of only an individual. And how then does a single genuine being determine the presence of many things and phenomena in this world?

Due to the emergence of this question, it should be assumed that the singularity of true reality is composite, collected from a multitude of individual, unchanging and truly real incorporeal formations, each of which independently determines the presence in the objective world of corresponding things or phenomena.

7. Consequently, each class (group) of sensory objects and phenomena of this not true world, in the true world, in the ideal world, corresponds to a certain “standard”, “type” or “idea” .

Thus, the authentic, truly real immaterial world consists of incorporeal, unchanging and eternal formations, eidos, ideas, through which matter receives its existence, its form and its quality.

8. Thus, matter exists because it imitates the world of ideas and joins it. Matter itself, without ideas, has neither form nor quality.

Therefore, sensible things owe their existence only to their participation in ideas. But in this communion, things cannot take from ideas all their perfection, since, being the world of things, they are not true, but therefore they are pale, imperfect copies of these ideas.

9. The world of ideas is organized hierarchically and in such a way that at the top of its hierarchy is the most important idea of the Good. The “place above the heavens” where the true immaterial reality, the world of ideas, is located is called Hyperurania.

10. The immortal soul of a person often flies into the world of ideas, remembers everything that it sees there, and then moves back into a person, who, if he seeks true knowledge, can only remember what the soul saw there.

The relationship between the world of ideas and the world of things is well clarified by Plato with the image of a cave. The philosopher compares people who believe in the reality and authenticity of the sensory picture of the material world with prisoners of a dungeon. From an early age they have shackles on their legs and necks, for this reason they cannot turn towards the entrance, and their gaze is turned deeper into the cave. Behind these people is a shining sun, the rays of which penetrate into the dungeon through a wide opening along its entire length and illuminate the wall, which is precisely where the prisoners’ gaze rests. Between the light source and the prisoners there is a road along which people move behind the screen, holding various utensils, figurines and other objects above the screen. The prisoners of the cave are unable to see anything except the shadows cast by the “road of life” on the wall of their gloomy abode. However, they believe that these shadows are the only true reality, that apart from their cave, the weak light and pale shadows in it, there is nothing else in the world. They do not believe one of them who, having managed to escape from the dungeon, and having seen real things, returns to them and tells them about the world outside the cave. Yes and all people live among the shadows, in a ghostly, unreal world. But there is another - the true world, and people can see it with the eyes of reason. A man who escapes from a cave and tells people about the true world is a philosopher. Bringing people the message of true peace is the true purpose of philosophy.

Eidos(Greek eidos - appearance, image, sample) - a term of ancient philosophy that fixes way of organizing an object

, as well as the categorical structure of medieval and modern philosophy, interpreting the original semantics of a given concept, respectively, in traditional and non-traditional contexts.

In ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of eidos was used to designate external structure: appearance as appearance (Milesian school, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, atomists). The relationship of eidos with the substrate arche acts as a fundamental semantic opposition to ancient philosophy, and the acquisition of eidos by a thing is actually thought of as its formation, which sets a close semantic connection between the concept of eidos and the concept of form (hylemorphism).

The fundamental initial design of the structural units of the universe is fixed by Democritus by designating the atom with the term “eidos”. The eidotic design of a thing is conceived in pre-Socratic natural philosophy as a result of the influence on the passive substantial principle of the active principle, embodying the pattern of the world and associated with mentality and goal-setting as carrying within itself the image (eidos) of the future thing (logos, Nus, etc.). In ancient Greek philosophy, language and culture as a whole, in this regard, the concept of E. turns out to be virtually equivalent from the point of view of semantics to the concept of idea (Greek idea - appearance, image, appearance, kind, method). And if the phenomenon of “substrate” is associated in ancient culture with the material (respectively, maternal) principle, then the source of “eidos” is with the paternal, masculine (idealism). If within the framework of pre-Socratic philosophy, eidos was understood as the external structure of an object, then in Plato the content of the concept of “eidos” is significantly transformed: first of all, eidos is understood not as external, but as internal form

, i.e. immanent way of being of an object. In addition, eidos acquires an ontologically independent status in Plato’s philosophy: the transcendental world of ideas or - synonymously - world of eidos How a set of absolute and perfect examples of possible things

. The perfection of eidos (= idea) is denoted by Plato through the semantic figure of the immobility of its essence (oysia), initially equal to itself (cf. “Being” among the Eleatics, whose self-sufficiency was recorded as immobility). The way of being of eidos, however, is its incarnation and embodiment in multiple objects structured in accordance with its gestalt ( eidos as a model) and therefore bearing in their structure and form ( eidos as a species) his image ( eidos as an image). In this context, the interaction between object and subject in the process of cognition is interpreted by Plato as communication (koinonia) between the eidos of the object and the soul of the subject

, the result of which is the imprint of eidos on the human soul, i.e. noema (noema) like conscious eidos

, - subjective eidos objective eidos

. (Parmenides).

In Aristotle’s philosophy, eidos is thought of as immanent in the material substrate of an object and inseparable from the latter (in the 19th century, this emphasis of Aristotle’s attitude was called hylemorphism). Any transformation of an object is interpreted by Aristotle as a transition from the deprivation of one or another eidos (accidental non-existence) to its acquisition (accidental formation). In Aristotle's taxonomy (in the field of logic and biology), the term "eidos" is also used in the meaning of "species" as a classification unit ("species" as a set of objects of a certain "species" as a method of organization) - in relation to the "genus" (genos). The term “eidos” is also used in a similar meaning in the tradition of ancient history (Herodotus, Thucydides).

Stoicism brings the concept of “eidos” closer to the concept of logos, emphasizing in it the creative, organizing principle (“spermatic logos”). Within the framework of Neoplatonism, “eidos” in the original Platonic sense is attributed to the One as his “thoughts” (Albinus), Nous as the Demiurge (Plotinus), and numerous eidos in the Aristotelian sense (as immanent gestalts of the object organization) - products of emanation .

The semantics of eidos as the archetypal basis of things is actualized in medieval philosophy:

archetipium as a prototype of things in the thinking of God in orthodox scholasticism;

John Duns Scotus about haecceitos (thisness) as a prior thing of her selfhood, actualized in the free creative will of God and in unorthodox directions of scholastic thought: the concept of species (the image is the Latin equivalent of eidos) in late Scotism;

presumption of visiones (mental images in Nicholas of Cusa), etc.

In late classical and non-classical philosophy, the concept of “eidos” finds a second wind: speculative forms of unfolding the content of the Absolute Idea before its objectification in the otherness of nature in Hegel; Schopenhauer's teaching about the "world of rational ideas"; Husserl's eidology (in Husserl's phenomenology is equivalent to essence), where species is conceived as an intellectual, but at the same time concretely given abstraction as a subject of “intellectual intuition”; concept of "ideas" E.I. Gaiser in neo-Thomism, etc.

In modern postmodern philosophy with its paradigmatic attitudes of “postmetaphysical thinking” and “postmodern sensitivity” (Postmetaphysical thinking, Postmodern sensitivity, Postmodernism), the concept of “eidos” is among those that are obviously associated with the tradition of metaphysics and logocentrism (logocentrism) and therefore are subject to radical criticism. This criticism turns out to be especially devastating in the context of the postmodern concept of simulacrum (Simulacrum, Simulation) and the “metaphysics of absence” constituted by postmodernism: thus, Derrida directly connects the traditionalist presumption of the “presence of a thing” with “the view of it as an eidos.”

Eidetic Sciences

- sciences of essence as opposed to sciences of external facts.

The phenomenological method includes eidetic reduction(bracketing) “world existence”, i.e. that individual existence of the contemplated object, which is determined by its place in the chain of natural phenomena. Through eidetic reduction, all scientific and non-scientific data of experience, judgment, position, evaluation related to the subject are excluded from the field of view, so that the essence of the subject becomes free and knowable.

Eidetics(from the Greek eidetike (episteme) - the science of what is seen) - 1) in psychology, the doctrine developed by Jensch about a completely definite (standing in connection with certain types of constitution) spiritual predisposition, which he called eidetic, which is observed in Ch. O. in children and adolescents;

Eidetics(from the Greek eidetike (episteme) - the science of what is seen) - 1) in psychology, the doctrine developed by Jensch about a completely definite (standing in connection with certain types of constitution) spiritual predisposition, which he called eidetic, which is observed in Ch. O. in children and adolescents;

2) the same as the doctrine of essence.

In modern psychology, the term “eidetism” denotes a characteristic of the phenomenon of memory associated with the extremely vivid clarity of the recorded object, within which the presentation is practically not inferior to direct perception according to the criteria of content detail and emotional and sensory richness.

Eidetic image (from Greek eidos - image) - unusually bright