Artificially created languages of the world. International artificial languages What are artificial languages examples

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF RUSSIA

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education

"Chelyabinsk State University"

(Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Chemical State University")

Kostanay branch

Department of Philology

COURSE WORK

Topic: International artificial languages

Moldasheva Aizhan Bolatovna

Specialty/direction Linguistics

Head of work

Kostanay 2013

Introduction. Language as a means of communication

1 The essence of language

2 Language as a social phenomenon. International artificial languages

Conclusion

Introduction

There are currently thousands of different languages. Language, as the most important means of human communication, is closely connected with society, its culture and people who live and work in society, using the language widely and diversely. Without considering the purpose of language, its connections with society, consciousness and human mental activity, without considering the rules of functioning and laws of the historical development of languages, it is impossible to deeply and correctly understand the system of language, its units of categories. The need for a language, a mediator between peoples, has always existed, but among the thousands of languages that cover our land, it is difficult to find just one that everyone can understand. For any natural language, the function of international communication is secondary, since such a language is primarily used as the national language of a particular people. Therefore, projects to create an artificial language were, as a rule, based on the idea of creating a universal language that would be common to all humanity or several ethnic groups.

The relevance of this work is due to the situation in which our society now finds itself. First of all, this is due to the development of global means of communication, primarily international negotiations. There are currently more than a thousand artificial languages in the world, and there is increasing interest in Esperanto and other planned languages. Therefore, it is possible that there will be an increase in interest in interlinguistics and planned languages as a means of communication, and as a consequence - the further development of this branch of linguistics. Today there are about five hundred artificial languages in use in the world. However, of all the planned languages that have ever been proposed as international languages, few have proven suitable for real communication and have come to be used by more or less people.

The purpose of this work: to study the role of artificial languages in the system of modern culture.

To achieve this goal, it is necessary to solve the following tasks:

give a brief historical background on the formation and development of artificial languages;

consider the varieties of international artificial languages;

expand the concept of “planned languages”.

Object of study: Basic English, Volapuk, Ido, Interlingua, Latin-Sine-Flexione, Loglan, Lojban, Na'vi, Novial, Occidental, Simlian, Solresol, Esperanto, Ifkuil, Klingon, Elvish languages.

Subject of research: Languages of artificial origin.

The theoretical significance of the study lies in the study of artificial language as a whole.

The practical significance of the study is how artificial languages help international communication and society as a whole.

The theoretical and methodological basis for the research was the fundamental work in the field of interlinguistics: Galen, J.M. Shleyer L.L. Zamenhof, E. Weferling, E. Lipman, K. Sjostedt, E. de Walem A. Gouda,

This paper examines the history, reasons, and advantages of artificial languages.

The work has a traditional structure and includes an introduction, a main part consisting of two chapters, a conclusion and a list of references.

I. Language as a means of communication

1 The essence of language

The history of the science of language indicates that the question of the essence of language is one of the most difficult in linguistics. It is no coincidence that it has several mutually exclusive solutions:

language is a biological, natural phenomenon that does not depend on humans ( Languages, these natural organisms formed in sound matter...., manifest their properties of a natural organism not only in the fact that they are classified into genera, species, subspecies, etc., but also in the fact that their growth occurs according to certain laws, - wrote A. Schleicher).

language is a mental phenomenon that arises as a result of the action of the individual spirit - human or divine ( Language, W. Humboldt wrote, is a continuous activity of the spirit, striving to transform sound into the expression of thought).

language is a psychosocial phenomenon, which, according to I.A. Baudouin de Courtenay collective - individual or collectively - mental an existence in which the individual is at the same time general, universal;

language is a social phenomenon that arises and develops only in a collective ( Language is a social element of speech activity, said F. de Saussure, external to the individual, who by himself cannot create language or change it).

It is easy to notice that in these different definitions, language is understood either as a biological (or natural) phenomenon, or as a mental (individual) phenomenon, or as a social (public) phenomenon. If we recognize language as a biological phenomenon, then it should be considered on a par with such human abilities as eating, drinking, sleeping, walking, etc., and considering that language is inherited by man, since it is inherent in his very nature. However, this contradicts the facts, since language is not inherited. It is acquired by the child under the influence of speakers. It is hardly legitimate to consider language a mental phenomenon that arises as a result of the action of the individual spirit - human or divine. In this case, humanity would have a huge variety of individual languages, which would lead to a situation of Babylonian confusion of languages, misunderstanding of each other, even by members of the same collective. There is no doubt that language is a social phenomenon: it arises and develops only in a team due to the need for people to communicate with each other.

Different understandings of the essence of language gave rise to different approaches to its definition, cf.: language is thinking expressed by sounds (A. Schleicher); language is a system of signs in which the only essential thing is the combination of meaning and acoustic image (F. de Saussure); language is practical, existing for other people and only thereby existing for myself, real consciousness (K. Marx, F. Engels); language is the most important means of human communication (V.I. Lenin); language is a system of articulate sounds of signs that spontaneously arises in human society and develops, serving for the purposes of communication and capable of expressing the entire body of knowledge and ideas of a person about the world (Artyunova N.D.).

Each of these definitions (and their number can be increased indefinitely) emphasizes different points: the relationship of language to thinking, the structural organization of language, the most important functions, etc., which once again indicates that language is a complex sign system, working in unity and interaction with human consciousness and thinking.

Language is a most complex phenomenon. E. Benveniste wrote several decades ago: “The properties of language are so unique that we can, in essence, talk about the presence of not one, but several structures in a language, each of which could serve as the basis for the emergence of integral linguistics.” Language is a multidimensional phenomenon that arose in human society: it is both a system and an anti-system, and an activity and a product of this activity, both spirit and matter, and a spontaneously developing object and an ordered self-regulating phenomenon, it is both arbitrary and produced, etc. By characterizing language in all its complexity from opposite sides, we reveal its very essence.

To reflect the complex essence of language, Yu. S. Stepanov presented it in the form of several images, because none of these images is capable of fully reflecting all aspects of language: 1) language as the language of an individual; 2) language as a member of the family of languages; 3) language as a structure; 4) language as a system; 5) language as type and character; 6) language as a computer; 7) language as a space of thought and as a “house of spirit” (M. Heidegger), i.e. language as a result of complex human cognitive activity. Accordingly, from the standpoint of the seventh image, language, firstly, is the result of the activity of the people; secondly, the result of the activity of a creative person and the result of the activity of language normalizers (states, institutions that develop norms and rules).

To these images at the very end of the 20th century. another one has been added: language as a product of culture, as its important component and condition of existence, as a factor in the formation of cultural codes.

From the position of the anthropocentric paradigm, a person understands the world through awareness of himself, his theoretical and substantive activities in it. No abstract theory can answer the question of why one can think of a feeling as fire and talk about the flame of love, the heat of hearts, the warmth of friendship, etc. Awareness of oneself as the measure of all things gives a person the right to create an anthropocentric order of things in his mind, which can be studied not at the everyday, but at the scientific level. This order, existing in the head, in the consciousness of a person, determines his spiritual essence, the motives of his actions, the hierarchy of values. All this can be understood by examining a person’s speech, those turns and expressions that he most often uses, to which he shows the highest level of empathy.

In the process of formation, the thesis was proclaimed as a new scientific paradigm: “The world is a collection of facts, not things” (L. Wittgenstein). Language was gradually reoriented to a fact, an event, and the focus was on the personality of the native speaker (linguistic personality, according to Yu. N. Karaulov). The new paradigm presupposes new settings and goals for language research, new key concepts and techniques. In the anthropocentric paradigm, the methods of constructing the subject of linguistic research have changed, the approach to the selection of general principles and methods of research has changed, and several competing metalanguages of linguistic description have appeared (R. M. Frumkina).

2 Language as a social phenomenon

As a social phenomenon, language is the property of all people belonging to the same group. Language is created and developed by society. F. Engels drew attention to this connection between language and society, writing in Dialectics of nature : Formed people came to the point that they had a need to say something to each other.

The question of the connection between language and society has different solutions. According to one point of view, there is no connection between language and society, because language develops and functions according to its own laws (Polish scientist E. Kurilovich), according to another, this connection is one-sided, because the development and existence of language is completely determined the level of development of society (French scientist J. Maruso) or vice versa - language itself determines the specifics of the spiritual culture of society (American scientists E. Sapir, B. Whorf). However, the most widespread point of view is that the connection between language and society is two-way.

A language that spontaneously arose in human society and is a developing system of discrete (articulate) sound signs, intended for communication purposes and capable of expressing the entire body of human knowledge and ideas about the world. The sign of spontaneity of emergence and development, as well as the limitlessness of the field of application and possibilities of expression, distinguishes Language from the so-called artificial, or formalized, languages that are used in other branches of knowledge (Artificial languages, Information languages, Programming language, Information retrieval language), and from various signaling systems created on the basis of the Language (Morse code, traffic signs, etc.). Based on the ability to express abstract forms of thinking and the associated property of discreteness (internal division of the message), language is qualitatively different from the so-called Animal Language, which is a set of signals that convey reactions to situations and regulate the behavior of animals in certain conditions. Animal communication can only be based on direct experience. It is indecomposable into distinctive elements and does not require a verbal response: the reaction to it is a certain course of action. Language proficiency is one of the most important features that distinguishes humans from the animal world. Language is at the same time a condition of development and a product of human culture.

Being primarily a means of expressing and communicating thoughts, language is most directly related to thinking. It is no coincidence that language units served as the basis for establishing forms of thinking. The connection between language and thinking is interpreted in different ways in modern science. The most widespread point of view is that human thinking can only occur on the basis of language, since thinking itself differs from all other types of mental activity in its abstractness. At the same time, the results of scientific observations by doctors, psychologists, physiologists, logicians and linguists show that thinking occurs not only in the abstract-logical sphere, but also in the course of sensory cognition, within which it is carried out by the material of images, memory and imagination; the thinking of composers, mathematicians, chess players, etc. is not always expressed in verbal form. The initial stages of the process of speech generation are closely related to various nonverbal forms of thinking. Apparently, human thinking is a combination of different types of mental activity, constantly replacing and complementing each other, but verbal thinking? only the main of these types. Since language is closely connected with the entire mental sphere of a person and the expression of thoughts is not its only purpose, it is not identical to thinking.

The connection with abstract thinking is provided by the linguistic ability, carrying out the communicative function, to convey any information, including general judgments, messages about objects that are not present in the speech situation, about the past and future, about fantastic or simply untrue situations. On the other hand, due to the presence in language of symbolic units expressing abstract concepts, language in a certain way organizes human knowledge about the objective world, dismembers it and consolidates it in human consciousness. Is this the second main function of language? the function of reflecting reality, i.e., the formation of categories of thought and, more broadly, consciousness. The interdependence of the communicative function of language and its connection with human consciousness was indicated by K. Marx: “Language is as ancient as consciousness; language is a practical consciousness, existing for other people and only thereby existing also for myself, real consciousness and, like consciousness, language arises only from the need, from the urgent need to communicate with other people.” Along with the two main languages, it performs a number of other functions: nominative, aesthetic, magical, emotionally expressive, appellative.

There are two forms of the existence of language, corresponding to the opposition of the concepts of “language” and speech. Language as a system has the character of a kind of code; speech is the implementation of this code. Language has special means and mechanisms for the formation of specific speech messages. The action of these mechanisms, for example, the assignment of a name to a specific object, allows the “old” language to be applied to the new reality, creating speech utterances. As one of the forms of social activity, speech has signs of consciousness and purposefulness. Without correlation with a specific communicative goal, a sentence cannot become a fact of speech. Communicative goals, which are universal in nature, are heterogeneous. Some actions and actions are unthinkable without speech acts. Speech is also involved in many other types of social activity. All forms of literary activity, propaganda, polemics, disputes, treaties, etc., arose on the basis of language and are carried out in the form of speech. With the participation of speech, the organization of work occurs, as well as many other types of social life of people.

Language has only its own characteristics that make it a unique phenomenon. In both forms of language existence, nationally specific and universal features are distinguished. Universal properties include all those properties of language that correspond to universal human forms of thinking and types of activity. Also universal are those properties of a language that allow it to fulfill its purpose, as well as those of its characteristics that arise as a consequence of development patterns common to all languages. Nationally specific ones include specific features of division, expression and internal organization of meanings.

The coincidence of structural features unites languages into types. The proximity of the material inventory of units, due to their common origin, unites languages into groups or families. The structural and material community that has developed as a result of linguistic contacts unites languages into linguistic unions.

The sign nature of language presupposes the presence in it of a sensually perceived form - expression, and some sensually not perceived meaning - content, materialized with the help of this form. Sound matter is the main and primary form of expression of meaning. Existing types of writing are only a transposition of sound form into a visually perceived substance. They are a secondary form of the plane of expression. Since sound speech unfolds in time, it has the characteristic of linearity, which is usually preserved in written forms.

The connection between the sides of a linguistic sign - the signifier and the signified - is arbitrary: one or another sound does not necessarily imply a strictly defined meaning, and vice versa. The arbitrariness of the sign explains the expression in different languages by different sound complexes of the same or similar meaning. Since the words of the native language isolate concepts, delimit them and consolidate them in memory, the connection between the sides of the sign for native speakers is not only strong, but also natural and organic.

The ability to relate sound and meaning is the essence of language. The materialistic approach to language emphasizes the inextricability of the connection between meaning and sound and at the same time its dialectically contradictory nature. Naturally developing languages allow variation in sounds that is not associated with a change in meaning, as well as a change in meaning that does not entail the need to vary the sound. As a result of this, different sequences of sounds can correspond to one meaning, and one sound? different meanings. Asymmetry in the relationship between the sound and semantic aspects of linguistic signs does not hinder communication, since the arsenal of means that perform a semantic-distinguishing role consists not only of constants that form a system of linguistic units, but also of many variables that a person uses in the process of expressing and understanding certain content. units, their syntactic position, intonation, speech situation, context, paralinguistic means - facial expressions, gestures.

In most languages, the following series of sound units is distinguished: a phoneme, in which acoustic features are fused due to the unity of pronunciation; a syllable combining sounds with an expiratory impulse; a phonetic word that groups syllables under one stress; a speech beat, combining phonetic words with the help of restrictive pauses, and, finally, a phonetic phrase, summing up the beats by the unity of intonation.

Along with the system of sound units, there is a system of sign units, formed in most languages by morpheme, word, phrase and sentence. Due to the presence of a language of meaningful units, various combinations of which create statements, and also due to the theoretical unlimitedness of the volume of a sentence, an infinite number of messages can be created from a finite set of initial elements.

The division of speech into sound elements does not coincide with its division into bilateral units. The difference in segmentation is determined not only by the fact that a syllable does not coincide in some languages with a morpheme, but also by the different depth of division of speech into sound and meaningful units: the limit of segmentation of a sound stream is a sound that does not have its own meaning. This ensures the possibility of creating a huge number of significant units differing in sound composition from a very limited inventory of sounds.

The sign, or semiotic, nature of language as a system suggests that it is organized by the principle of distinctiveness of the units that form it. With minimal differences in sound or meaning, language units form oppositions based on a certain characteristic. Opposed units are in paradigmatic relationships with each other, based on their ability to differentiate in the same speech position. Contiguity relationships also arise between language units, determined by their ability to be compatible.

The transmission of information by language can be considered not only from the point of view of the organization of its internal structure, but also from the point of view of the organization of its external system, since the life of a language is manifested in socially typified forms of its use. The social essence of language ensures its adequacy to the social order.

The influence of language on the development of social relations is evidenced, first of all, by the fact that language is one of the consolidating factors in the formation of a nation. It is, on the one hand, a prerequisite and condition for its occurrence, and on the other, the result of this process. In addition, this is evidenced by the role of language in the educational and educational activities of society, since language is a tool and means of transmitting knowledge, cultural, historical and other traditions from generation to generation.

The connection between language and society is objective, independent of the will of individuals. However, it is also possible to have a purposeful influence of society (and in particular, the state) on a language when a certain language policy is carried out, that is, a conscious, purposeful influence of the state on the language, designed to facilitate its effective functioning in various spheres (most often this is expressed in the creation of alphabets or writing for unliterate peoples, in the development or improvement of spelling rules, special terminology, codification and other types of activities, although sometimes the language policy of the state can hinder the development of the national literary language as it was.

Any thought in the form of concepts, judgments or conclusions is necessarily clothed in a material-linguistic shell and does not exist outside of language. It is possible to identify and explore logical structures only by analyzing linguistic expressions.

Language is a sign system that performs the function of forming, storing and transmitting information in the process of understanding reality and communication between people.

Language is a necessary condition for the existence of abstract thinking. Therefore, thinking is a distinctive feature of a person.

According to their origin, languages are natural and artificial.

Natural languages are audio (speech) and then graphic (writing) information sign systems that have historically developed in society. They arose to consolidate and transfer accumulated information in the process of communication between people. Natural languages act as carriers of centuries-old culture and are inseparable from the history of the people who speak them.

Everyday reasoning is usually conducted in natural language. But such a language developed in the interests of ease of communication, the exchange of thoughts at the expense of accuracy and clarity. Natural languages have rich expressive capabilities: with their help you can express any knowledge (both ordinary and scientific), emotions, feelings.

Natural language performs two main functions - representational and communicative. The representative function is that language is a means of symbolic expression or representation of abstract content (knowledge, concepts, thoughts, etc.), accessible through thinking to specific intellectual subjects. The communicative function is expressed in the fact that language is a means of transmitting or communicating this abstract content from one intellectual subject to another. The letters, words, sentences themselves (or other symbols, such as hieroglyphs) and their combinations form the material basis in which the material superstructure of the language is realized - a set of rules for constructing letters, words, sentences and other language symbols, and only together with the corresponding superstructure does it or another material basis forms a specific natural language.

II. International artificial languages

1 The main stages of the development of artificial languages

Today, about five hundred artificial languages operate more or less successfully in the world. At the same time, we do not take into account extreme and degenerate cases - such as chemical notation, musical notation or flag alphabet. We are talking only about developed languages suitable for conveying complex concepts. Projects to create an artificial language, as a rule, were based on the idea of creating a universal language that would be common to all humanity or several ethnic groups. Obviously, any project of creating a pan-human language is political.

The first attempt to create an artificial language known to us was made in the 2nd century AD. Greek physician Galen. In total, about a thousand international artificial language projects have been created in the history of mankind. However, very few of them have received any practical application. The first artificial language that truly became a means of communication between people was created in 1879 in Germany by J.M. Schleyer, Volapuk. Due to the extreme complexity and detail of its grammar, Volapuk was not widely used in the world and finally fell out of use around the middle of the 20th century. A much happier fate awaited L.L., invented in 1887. Zamenhof language Esperanto. Creating his own language, L.L. Zamenhof sought to make it as simple and easy to learn as possible. He succeeded. Esperanto spelling is based on the principle of “one sound - one letter”. Nominal inflection is limited to four, and verbal inflection to seven forms. The declension of names and the conjugation of verbs are unified, in contrast to natural national languages, where, as a rule, we encounter several types of declension and conjugation. Mastering the Esperanto language usually takes no more than a few months. There is a wealth of original and translated fiction in Esperanto, numerous newspapers and magazines are published (about 40 periodicals), and radio broadcasting is conducted in some countries. Esperanto, along with French, is an official language of the International Postal Association. Among the artificial languages that have received some practical use are also Interlingua (1903), Occidental (1922), Ido (1907), Novial (1928), Omo (1926) and some others. However, they have not received wide distribution. Of all the currently existing artificial languages, only Esperanto has a real chance of becoming over time the main means of international communication. All artificial languages are divided into a posteriori and a priori. A posteriori are such artificial languages that are composed “on the model and from the material of natural languages.” Examples of a posteriori languages include Esperanto, Latin-sine-flexione, Novial, and Neutral idiom. A priori are those artificial languages whose vocabulary and grammar are in no way related to the vocabulary and grammar of natural languages, but are built on the basis of principles developed by the creator of the language. Examples of a posteriori languages are solresol and rho. .

An ideal description of artificial language as a political project is given by Orwell in his famous novel 1984. According to one version, the idea of a powerful newspeak, which serves as the main basis of a totalitarian society, was inspired by Esperanto by Orwell. Newspeak cannot be called a full-fledged artificial language, but the methodology for its creation is described by Orwell so completely that anyone can construct a fully functional Newspeak for their own needs.

Newspeak is an excellent example of a fictional language developed enough to transcend the binding of a book. Fortunately, not all literary languages are intended to build totalitarianism, completely freed from thought crimes and evil sex. Among our contemporaries there are several thousand people who are able to speak quite clearly in the language of the Quenya elves or in the secret dialect of the Khuzdul dwarves. (We note, however, that there are still more fans of independent newspeak - turn on the TV and see for yourself). Tolkien's Middle-earth saga, which gained new popularity after the release of the cinematic trilogy "The Lord of the Rings", is built on languages constructed by the Professor. We owe the entire story of the adventures of the hobbits to Tolkien's project to develop a family of special languages. The project was so successful that the resulting languages took on a life of their own. No less popular is the fantastic language Klingon - the spoken and written language of the Klingon Empire, described in the Star Trek series. Klingon was developed by American linguist Mark Orkand for Paramount Studios. For the inhabitants of the Earth who want to study Klingon, a special institute of the Klingon language has been founded, books and magazines are published. Klingon is a developed and living language. Not long ago, Earth's main search engine, Google, opened a Klingon version of its home page. This is an absolute indicator of the importance of the Klingon language for civilization. To a lesser extent, the general public knows the artificial language described by Jorge Luis Borges in the short story “Tlen, Ukbar, Orbistertius”; in this small work, the constructions of the new language are practically not spelled out, but the mechanisms of influence of the artificial language on the work of the social machine are revealed. (In addition to the aforementioned short story "Tlen, Ukbar, Orbistertius", Borges's lesser-known story "The Analytical Language of John Wilkes" is devoted to the problem of constructing an artificial language and the general typology of concepts.) The most successful project to build an artificial language is the creation of Hebrew - a living language for a dynamic, modern nation based on written Hebrew. Hebrew ceased to be a spoken language around the 2nd century BC. For the next 18 centuries, Hebrew served as the written language of theological and scientific texts. Yiddish and, to a lesser extent, Ladino became the common spoken language for Jews. In the 19th century, the political project of Jewish statehood demanded the creation of a universally recognized national language. Hebrew was reconstructed as a spoken language. First of all, it was necessary to develop new phonetics and introduce vocabulary to denote concepts that were absent in Biblical Hebrew. In addition, the new language was subject to the requirement that it should be relatively easy for Jews to learn.

In popular typologies of artificial languages, one often comes across the section “machine languages”. I want to draw your attention to the fact that programming languages - C, C++, Basic, Prolog, HTML, Python etc. are not machine languages in the ordinary sense of the word. C++ code is as alien to a computer as Pushkin’s poems or the slang of American blacks. Real machine language is binary code. It cannot be said that binary codes are fundamentally inaccessible to people; after all, it was people who constructed them on the basis of mathematical apparatus. Artificial machine language is intended for people rather than machines - it is only a way to formalize instructions for a computer so that special programs can translate them into codes.

Artificial languages are special languages that, unlike natural ones, are constructed purposefully. They can be constructed using natural language or a previously constructed artificial language. A language that acts as a means of constructing or learning another language is called a metalanguage, the basis is a language-object. A metalanguage, as a rule, has richer expressive capabilities compared to an object language.

The following types of artificial languages are distinguished:

Programming languages and computer languages are languages for automatic information processing using a computer.

Information languages are languages used in various information processing systems.

Formalized languages of science are languages intended for symbolic recording of scientific facts and theories of mathematics, logic, chemistry and other sciences.

Languages of non-existent peoples created for fictional or entertainment purposes, for example: the Elvish language, invented by J. Tolkien, the Klingon language, invented by Marc Okrand for the science-fiction series "StarTrek", the Na'vi language, created for the film "Avatar".

International auxiliary languages are languages created from elements of natural languages and offered as an auxiliary means of international communication.

The most famous artificial languages are: Basic English, Volapuk, Ido, Interlingua, Latin Blue Flexione, Loglan, Lojban, Na'vi, Novial, Occidental, Simlian, Solresol, Esperanto, Ifkuil, Klingon, Elvish languages.

Any artificial language has three levels of organization:

· syntax is the level of language structure where relationships between signs, methods of formation and transformation of sign systems are formed and studied;

· cinematics, where the relationship of a sign to its meaning (meaning, which is understood as either the thought expressed by the sign or the object denoted by it) is studied;

· pragmatics, which examines the ways in which signs are used in a given community using an artificial language.

However, the pathos of the “destruction of the Tower of Babel” is so strong that the political meaning and background of artificial language projects is very difficult to isolate from later descriptions. The most successful and most failed project of a language of international communication is Esperanto. It should be noted that most of the descriptions of Esperanto were created by fans of the new language. There is no hint in the propaganda texts about the structure and goals of the Esperanto project, however, could an artificial language have become almost native to several million people if it had not been included in a single program? I called Esperanto the most failed project of a universal language. This is not an accident - despite the fact that several million people speak Esperanto, this language is not common to them. A Russian-speaking Esperantist practically does not understand an English or Spanish speaker. An artificial living language develops with each “diaspora” and spreads into dialects. The development of the Esperanto project is not explained by the functional role of the new language for international communication.

2 Classification of international artificial languages

iconic international artificial language

International artificial languages are the object of study of two interdisciplinary theories: the theory of international languages (international in language) and the theory of artificial languages (artificial in language). The first theory is known as interlinguistics; the second theory is still in the process of formation and has not isolated itself from adjacent disciplines.

The first aspect of the study of international artificial languages is mainly sociolinguistic: International artificial languages are studied from the point of view of their social functioning and are considered in parallel with other phenomena united by the common problem of “language and society”: bilingualism, interference of languages, the problem of spontaneous and conscious in language , issues of language policy, etc. The second aspect is mainly lingo-semiotic: the ontological characteristics of international artificial languages, their similarities and differences from other sign systems, and the typological basis for the classification of international artificial languages are examined here.

The typological classification of international artificial languages is based on a hierarchically organized system of features, the number of which (and therefore the depth of classification) can in principle be infinite - up to the formation of classes of international artificial languages consisting of one language. We limit ourselves here to considering typological features that relate only to the upper tiers of the hierarchy. The initial classification criterion can be recognized as the relationship between international artificial languages and natural languages in terms of expression.

According to tradition, dating back to the works of G. Mock, but even more to the famous works of L. Couture and L. Lo, all international artificial languages are divided into two classes depending on the presence/absence of their material correspondence to natural languages. A posteriori language is an artificial language, the elements of which are borrowed from existing languages, as opposed to an a priori, artificial language, the elements of which are not borrowed from existing languages, but are created arbitrarily or on the basis of some logical (philosophical) concept.

A posteriori languages can be divided into three classes:

Simplified ethnic language: Basic English, Latin Blue Flexion, etc.;

Naturalistic language, i.e., as close as possible to ethnic languages (usually the Romance group): Occidental, Interlingua;

Autonomous (schematic) - in which the grammar with a priori elements uses vocabulary borrowed from ethnic languages: Esperanto and most Esperantoids, late Volapuk.

Examples of a priori languages can be: Solresol, Ithkuil, Ilaksh, Loglan, Lojban, Rho, Mantis, Chengli, Asteron, Dyryar. The presence of a priori elements at the syntagamatic level (combinability of morphemes) determines that the a posteriori language belongs to an autonomous type; Based on their presence at the paradigmatic level (composition of morphemes), autonomous languages can be divided into hyperschematic (Esperanto) and hyposchematic (neutral idiom).

The contrast between these two classes of international artificial languages is not absolute, but relative: in a posteriori languages, some a priori elements can be used, and in a priori languages, a posterioriisms are sometimes found.

Due to the fact that the ratio of a priori and a posteriori features is not the same in individual international artificial languages, the opposition of these classes takes the form of a continuum, the middle link of which will be languages with an approximately equal ratio of a priori and a posteriori features. The projects of this group were given the name mixed languages by L. Couture and L. Lo, including Volapuk and similar projects. However, an unambiguous definition of mixed languages has not yet been given, which has led to significant arbitrariness in the use of this term. So, for example, in one of the classifications mentioned by M. Monroe-Dumain, Volapuk is assigned to the a posteriori group, while some projects close to him were included in the mixed group. Our position on this issue will be formulated below.

Some corrections to the scheme of L. Couture and L. Law should be made due to the fact that in the time that has passed since the publication of their work, projects have been created and received a certain spread that expanded the limits of the specified continuum towards greater a posterioriity (Latin-blue- Flexione, 1903; Occidental, 1922; Interlingua-IALA, 1951, etc.). In contrast to languages like Esperanto, these international artificial languages use exclusively natural forms, refusing to use apriorisms, and also differ in other features, which will be discussed in more detail below. Thus, a posteriori projects began to differ in the degree of a posterioriity: international artificial languages that tend toward complete, absolute a posterioriity are usually called naturalistic; international artificial languages that exhibit a predominant (dominant) a posteriori nature are called autonomous or schematic.

The need for additional changes in the classification of L. Couture and L. Lo is caused by the fact that after the decline of Volapukoid, starting from the last decade of the 19th century, projects began to appear that represented either a correction of the previously created international artificial languages (reform projects: first Volapukoids, and then Esperantoids, of which the most famous is ido, which gave its own series of successors - idoid projects), or an attempt to synthesize several projects (compromise projects, for example, the projects of E. Weferling, E. Lipman, K. Sjöstedt, etc.). Thus, in addition to the “primary” international artificial languages, directly traceable (or not) to natural languages, “secondary” international artificial languages arose, the source of which is no longer natural languages, but previously created international artificial languages. A series of projects building on the same international artificial languages form “families” of languages (sometimes intersecting with each other). These genealogical associations could become the subject of special, interlinguistic, comparative studies.

The next classification feature relates to the structure of the sign in international artificial languages. International artificial languages can be divided into several groups depending on how the ratio of the inventory of morphemes and the inventory of words is built in them.

International artificial languages differ primarily in the very set of sign levels. International artificial languages such as Ido have the same levels as natural languages of the synthetic type: the levels of roots, complex stems (root + root), derived stems (root + derivator) and word forms (stem + grammatical indicator). Grammatical indicators in Ido have a syncretic character, being both a sign of a given part of speech and an exponent of a certain categorical meaning: rich-o “rich man” (-o is a sign of a singular noun), rich-i “rich people” (-i is a sign of a plural noun . numbers), rich-a “rich” or “rich” (-a is a sign of an adjective not differentiated by numbers).

In most cases, the principles of the structure of morphemes in a posteriori projects are subject to different laws than in a priori international artificial languages.

A posteriori languages are divided into sign-related subgroups depending on their lexical homogeneity or heterogeneity.

We have lexically homogeneous languages if the choice of morphemes (words) was made from a single source.

International artificial languages with heterogeneous vocabulary are the result of combining vocables that do not occur together within natural lexical systems. Examples are the Anglo-Franca project, 1889, built on the root word of English and French, and the anti-Babilon project, 1950, which used the vocabulary of 85 languages of Europe, Asia and Africa.

A planned language is an international artificial socialized language, that is, a language created for international communication and used in practice.

The main international artificial languages that have or have had communicative implementation.

Volapyuk - created in 1879 by I.M. Schleyer, Litzelstetten near Konstanz (Germany); active use of the language continued until approximately 1893, when, having noted the failure of Volapyuk, its academy began to develop a new artificial language (neutral idiom); The last Volapyuk magazine was discontinued in 1910.

Esperanto - created in 1887 by L. L. Zamenhof, Warsaw (Poland, then part of the Russian Empire); the most common planned language, actively used to this day.”

Idiom-neutral - created in 1893-1898. International Volapuk Academy under the leadership of V. K-Rosenberger, St. Petersburg (Russia); was the official language of the named academy in 1908, had small groups of supporters in Russia, Germany, Belgium and the USA. In 1907, when artificial languages were considered by the Delegation Committee for the adoption of an international auxiliary language [see 15, p. 71 et seq.] the neutral idiom emerged as the main rival of Esperanto; after the committee spoke in favor of (reformed) Esperanto, the propaganda of neutral idioms ceases; the last magazine (Progres, St. Petersburg) was published until 1908.

Latino-sine-flexione created in 1903, G. Peano, Turin (Italy); in 1909 it was adopted as the official language by the former Volapuk Academy (which became known as the Academy of International Language - Academia pro Interlingua); was used in a number of scientific publications until the outbreak of the Second World War (1939), after which it gradually faded away.

Ido (reformed Esperanto) - created in 1907-1908. committee and standing commission of the Delegation for the adoption of an international auxiliary language under the leadership of L. Couture and with the participation of L. de Beaufront, O. Jespersen and V. Ostwald; was a strong competitor to Esperanto until its crisis in 1926-1928. Currently it has supporters and periodicals in Switzerland, England, Sweden and a number of other countries.

Occidental - created in 1921-1922. E. de Valem, Revel (now Tallinn, Estonia); starting in 1924, he began to adopt supporters from the Ido language; had groups supporting him in Austria, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, France and some other countries; After the publication of the Interlingua language in 1951, most of the Occidentalists switched to the position of this language.

Novial - created in 1928 by O. Jespersen, Copenhagen (Denmark). He had a limited circle of supporters, mainly from among the former Idists; Novialist groups disintegrated with the outbreak of World War II.

Interlingua - created in 1951 by the International Auxiliary Language Association under the leadership of A. Goud, New York (USA). The initial composition of supporters was formed due to the transition to this language of former adherents of Occidental and Ido. Currently it has periodicals in Denmark, Switzerland, France, Great Britain and some other countries.

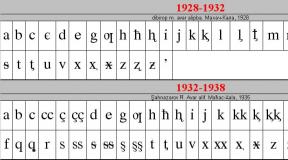

The above list did not include some of the planned languages that had a small number of supporters (reform-neutral, 1912; reformed Volapyuk, 1931; neo, 1937) or stood aside from the main line of development of interlinguistics (basic English, 1929-1932).

Within the framework of the global linguistic situation, planned languages, along with other artificial ones, are included in the general system of interaction between natural and artificial languages. Researchers of the linguistic situation of the modern world note as its characteristic feature the parallel existence of natural and artificial languages, due to the scientific and technological revolution. Electronic computers (computers) that appeared in the 50s required the development of special artificial languages in which it was possible to formulate commands to control the activities of the computer (programming languages) or to record information entered into the computer and to be processed (information languages).

As the scope of computer use expanded, an increasing number of programming languages and information languages were developed, and an ever-increasing number of personnel (programmers, computer science specialists) were involved in working with them, not to mention the numerous consumers of information that had undergone machine processing on a computer. As a result, rapidly developing artificial languages formed “their own unique world, existing in parallel with the world of natural languages,” and “a new linguistic situation began to emerge, the main difference of which can be considered the formation of natural-artificial bilingualism in society.”

The foregoing clarifies the historical significance of the appearance at the end of the 19th century. planned languages as the first messengers of the modern linguistic situation, consisting of the interaction of two linguistic worlds, the world of natural languages that accompanied humanity at all stages of its existence, and the world of artificial languages that has formed over the last century.

Conclusion

Having studied the topic “International artificial languages”, we came to the conclusion that an artificial language is as important as a natural one. Since, various international negotiations take place in a certain language, relating to a certain nation.

Multilingualism has always been a problem in international cooperation and in the progress of world culture. This is especially acute in our time, when the number of international organizations is rapidly increasing and international business contacts are expanding.

Language is defined as a means of human communication. This one of the possible definitions of language is the main thing, because it characterizes the language not from the point of view of its organization, structure, etc., but from the point of view of what it is intended for. But why is it important? Are there other means of communication? Yes, they do exist. An engineer can communicate with a colleague without knowing his native language, but they will understand each other if they use drawings. Drawing is usually defined as the international language of engineering. The musician conveys his feelings through melody, and the listeners understand him. The artist thinks in images and expresses this through lines and color. And all these are “languages”, so they often say “the language of a poster”, “the language of music”. But this is a different meaning of the word language.

Despite the fact that scientists are still rather indifferent to the issue of an auxiliary international language, and most of all supporters of artificial languages, and mainly artificial languages, are recruited in the scientific world between mathematicians and natural scientists, the topic of international artificial languages remains relevant.

Based on the goals and objectives of this work, we can conclude that international artificial languages have their own specific role in society and in the system of modern culture, which are created on the basis of natural languages for the accurate and economical transmission of scientific and other information. They are widely used in modern science and technology: chemistry, mathematics, theoretical physics, computer technology, cybernetics, communications, shorthand, as well as in legal and logical science for theoretical and practical analysis of mental structures.

We believe that the development of an international artificial language will give an advantage to the cooperation of political negotiations for the negotiation of international transactions. But the main advantage is the desire of a person in modern society to study not only natural languages, but also languages of artificial origin.

List of used literature

1.Bally, Sh., General linguistics and issues of the French language, trans. from French, [Text] / Sh. Bally - M., 1955-p.77.

2.Baudouin de Courtenay, A., Selected works on general linguistics, [Text] / A. Baudouin de Courtenay - vol. 2, M., 1963-365s

.Vendina, T.I. Introduction to linguistics - State Unitary Enterprise Publishing House "Higher School", [Text] / T.I. Vendina - M., 2001 - 22-23s.

.Vinogradov, V.V., Problems of literary languages and patterns of their formation and development, [Text] / V.V. Vinogradov - M., 1967-111p.

.Zvegintsev V. A., History of linguistics [Text] / XIX ? XX centuries in essays and extracts/V.A. Zvegintsev 3rd ed., part 2, M., 1965 2001.105c.

6.Kodukhov, V.I. Introduction to linguistics [Text] / V.I. Kodukhov. - 2nd ed., revised. and additional V.I. Kodukhov - M.: Education, 1987. - 98c.

.Kuznetsov S. N. Theoretical foundations of interlinguistics. - [Text] / S.N. Kuznetsov - M.: Peoples' Friendship University, 1987-254p.

.Kuznetsov S.N. International languages; Artificial languages. - Linguistic encyclopedic dictionary. [Text] / S.N. Kuznetsov - M.: 1990-314 p.

9.Leontyev A.A. What is language. [Text] / A.A. Leontiev - M.: Pedagogy - 1976-22p.

.Marx K. and Engels F., [Text] / K. Marx and F. Engels - Works, 2nd ed., vol. 3, p. 29

.Maslov Yu.S. Introduction to linguistics: a textbook for philology. and linguistics fak. universities / Yu.S. Maslov. [Text] / 5th ed., erased. - M.: IC Academy, Phil. fak. St. Petersburg State University, 2006. - 215 p.

.Maslov. Yu.S. Introduction to linguistics - [Text] / Yu.S. Maslov - M. Publishing center "Academy" 2006.-52p.

.Maslova V.A. Linguoculturology - [Text] / Publishing Center "Academy" / V.A. Maslova - M., 2001 - 8-9 p.

.International artificial languages [Electronic resource] // #"justify">. International languages [Electronic resource] // #"justify">. Mechkovskaya N.B. Social linguistics / N.B. Mechkovskaya - [Text] Aspect Press/N.B. Mechkovskaya - 1996. - 411 p.

.Garbage. A.Yu. Fundamentals of the science of language - [Text] / Novosibirsk / A.Yu. Musorin - M., 2004 - 180 p.

.Rozhdestvensky Yu.V. Introduction to linguistics: a textbook for students of philological faculties of higher educational institutions / Yu.V. Christmas. -[Text] / M.: IC Academy, 2005. - 327 p.

.Skvortsov L.I. Language, communication and culture / Russian language at school. [Text] / L.I. Skvortsov-No. 1 - 1994. - 134 p.

.Saussure F. de. Transactions on linguistics, trans. from French, [Text] / F.de. Syussor - M., 1977 - 92 p.

.Formanovskaya N.I. Culture of communication and speech etiquette / Russian language at school. [Text] / N.I. Formanovskaya - No. 5 - 1993. - 93s

Tutoring

Need help studying a topic?

Our specialists will advise or provide tutoring services on topics that interest you.

Submit your application indicating the topic right now to find out about the possibility of obtaining a consultation.

Linguists, there are about 7,000 languages. But this is not enough for people - they come up with new ones over and over again. In addition to such famous examples as Esperanto or Volapük, many other artificial languages have been developed: sometimes simple and fragmentary, and sometimes extremely ingenious and elaborate.

Humanity has been creating artificial languages for at least a couple of millennia. In antiquity and the Middle Ages, “unearthly” language was considered divinely inspired, capable of penetrating the mystical secrets of the universe. The Renaissance and Enlightenment witnessed the emergence of a whole wave of “philosophical” languages, which were supposed to connect all knowledge about the world into a single and logically impeccable structure. As we approached modern times, auxiliary languages became more popular, which were supposed to facilitate international communication and lead to the unification of humanity.

Today, when talking about artificial languages, people often remember the so-called artlangs- languages that exist within works of art. These are, for example, Tolkien’s Quenya and Sindarin, the Klingo language of the inhabitants of the Star Trek universe, the Dothraki language in Game of Thrones, or the N’avi language from James Cameron’s Avatar.

If we take a closer look at the history of artificial languages, it turns out that linguistics is by no means an abstract field where only intricate grammars are dealt with.

Utopian expectations, hopes and desires of humanity were often projected precisely into the sphere of language. Although these hopes usually ended in disappointment, there are many interesting things to be found in this story.

1. From Babylon to angelic speech

The diversity of languages, which complicates mutual understanding between people, has often been interpreted in Christian culture as a curse from God sent to humanity as a result of the Babylonian Pandemonium. The Bible tells about King Nimrod, who set out to build a gigantic tower whose top would reach to the sky. God, angry at proud humanity, confused their language so that one ceased to understand the other.

It is quite natural that dreams of a single language in the Middle Ages were directed to the past, and not to the future. It was necessary to find a language before confusion - the language in which Adam spoke with God.

The first language spoken by humanity after the Fall was considered to be Hebrew. It was preceded by the very language of Adam - a certain set of primary principles from which all other languages arose. This construction, by the way, can be correlated with the theory of generative grammar by Noam Chomsky, according to which the basis of any language is a deep structure with general rules and principles for constructing statements.

Many church fathers believed that the original language of mankind was Hebrew. One notable exception is the views of Gregory of Nyssa, who sneered at the idea of God as a school teacher showing the first ancestors the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. But in general, this belief persisted in Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

Jewish thinkers and Kabbalists recognized that the relationship between an object and its designation is the result of an agreement and a kind of convention. It is impossible to find anything in common between the word “dog” and a four-legged mammal, even if the word is pronounced in Hebrew. But, in their opinion, this agreement was concluded between God and the prophets and is therefore sacred.

Sometimes discussions about the perfection of the Hebrew language go to extremes. The 1667 treatise A Brief Sketch of the True Natural Hebrew Alphabet demonstrates how the tongue, palate, uvula, and glottis physically form the corresponding letter of the Hebrew alphabet when pronounced. God not only took care to give man a language, but also imprinted its structure in the structure of the speech organs.

The first truly artificial language was invented in the 12th century by the Catholic abbess Hildegard of Bingen. A description of 1011 words has come down to us, which are given in hierarchical order (words for God, angels and saints follow at the beginning). Previously it was believed that the author intended the language to be universal.

But it is much more likely that it was a secret language intended for intimate conversations with angels.

Another “angelic” language was described in 1581 by occultists John Dee and Edward Kelly. They named him Enochian(on behalf of the biblical patriarch Enoch) and described the alphabet, grammar and syntax of this language in their diaries. Most likely, the only place where it was used was the mystical sessions of the English aristocracy. Things were completely different just a couple of centuries later.

2. Philosophical languages and universal knowledge

With the beginning of modern times, the idea of a perfect language experienced a period of growth. Now they are no longer looking for it in the distant past, but are trying to create it themselves. This is how philosophical languages are born, which have an a priori nature: this means that their elements are not based on real (natural) languages, but are postulated, created by the author literally from scratch.

Typically, the authors of such languages relied on some natural science classifications. Words here can be built on the principle of chemical formulas, when the letters in a word reflect the categories to which it belongs. According to this model, for example, the language of John Wilkins is structured, who divided the whole world into 40 classes, within which separate genera and species are distinguished. Thus, the word “redness” in this language is expressed by the word tida: ti - designation of the class “perceptible qualities”, d - the 2nd kind of such qualities, namely colors, a - the 2nd of colors, that is, red.

Such a classification could not do without inconsistencies.

It was precisely this that Borges sneered at when he wrote about animals “a) belonging to the Emperor, b) embalmed, h) included in this classification, i) running around like crazy,” etc.

Another project to create a philosophical language was conceived by Leibniz - and ultimately embodied in the language of symbolic logic, the tools of which we still use today. But it does not pretend to be a full-fledged language: with its help, you can establish logical connections between facts, but not reflect these facts themselves (not to mention using such a language in everyday communication).

The Age of Enlightenment put forward a secular ideal instead of a religious one: new languages were supposed to become assistants in establishing relations between nations and help bring peoples closer together. "Pasigraphy" J. Memieux (1797) is still based on a logical classification, but the categories here are chosen on the basis of convenience and practicality. Projects for new languages are being developed, but the proposed innovations are often limited to simplifying the grammar of existing languages to make them more concise and clear.

However, the desire for universalism is sometimes revived. At the beginning of the 19th century, Anne-Pierre-Jacques de Wim developed a project for a musical language similar to the language of angels. He suggests translating sounds into notes, which, in his opinion, are understandable not only to all people, but also to animals. But it never occurs to him that the French text encrypted in the score can only be read by someone who already knows at least French.

The more famous musical language received a melodic name solresol, the draft of which was published in 1838. Each syllable is indicated by the name of a note. Unlike natural languages, many words differ by just one minimal element: soldorel means “to run”, ladorel means “to sell”. Opposite meanings were indicated by inversion: domisol, the perfect chord, is God, and its opposite, solmido, denotes Satan.

Messages could be sent to Solresol using voice, writing, playing notes or showing colors.

Critics called Solresol "the most artificial and most inapplicable of all a priori languages." In practice, it was really almost never used, but this did not prevent its creator from receiving a large cash prize at the World Exhibition in Paris, a gold medal in London and gaining the approval of such influential persons as Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Alexander von Humboldt. The idea of human unity was too tempting. It is precisely this that the creators of new languages will pursue in later times.

3. Volapuk, Esperanto and European unification

The most successful linguistic construction projects were not intended to comprehend divine secrets or the structure of the universe, but to facilitate communication between peoples. Today this role has been usurped by English. But doesn't this infringe on the rights of people for whom this language is not their native language? It was precisely this problem that Europe faced at the beginning of the 20th century, when international contacts intensified and medieval Latin had long fallen out of use even in academic circles.

The first such project was Volapuk(from vol "world" and pük - language), developed in 1879 by the German priest Johann Martin Schleyer. Ten years after its publication, there are already 283 Volapukist clubs around the world - a success previously unseen. But soon not a trace remained of this success.

Except that the word “volapyuk” has firmly entered the everyday lexicon and has come to mean speech consisting of a jumble of incomprehensible words.

Unlike the “philosophical” languages of the previous formation, this is not an a priori language, since it borrows its foundations from natural languages, but it is not completely a posteriori, since it subjects existing words to arbitrary deformations. According to the creator, this should have made Volapuk understandable to representatives of different language groups, but in the end it was incomprehensible to anyone - at least without long weeks of memorization.

\the most successful linguistic construction project was and remains Esperanto. A draft of this language was published in 1887 by the Polish ophthalmologist Ludwik Lazar Zamenhof under the pseudonym Dr. Esperanto, which in the new language meant “Hopeful.” The project was published in Russian, but quickly spread first throughout the Slavic countries and then throughout Europe. In the preface to the book, Zamenhof says that the creator of an international language needs to solve three problems:

Dr. Esperanto

from the book “International Language”

I) That the language should be extremely easy, so that it can be learned jokingly. II) So that everyone who has learned this language can immediately use it to communicate with people of different nations, no matter whether this language is recognized by the world and whether it finds many adherents or not.<...>III) Find means to overcome the indifferentism of the world and to encourage it as soon as possible and en masse to begin to use the proposed language as a living language, and not with a key in hand and in cases of extreme need.

This language has a fairly simple grammar, consisting of only 16 rules. The vocabulary is made up of slightly modified words that have common roots for many European peoples in order to facilitate recognition and memorization. The project was a success - today, according to various estimates, experanto speakers range from 100 thousand to 10 million people. More importantly, a number of people (about a thousand people) learn Esperanto in the early years of life, rather than learning it later in life.

Esperanto attracted a large number of enthusiasts, but it did not become the language of international communication, as Zamenhof had hoped. This is not surprising: language can take on such a role due not to linguistic, but to the economic or political advantages that stand behind it. According to the famous aphorism, “a language is a dialect that has an army and a navy,” and Esperanto had neither.

4. Extraterrestrial intelligence, elves and Dothraki

Among later projects stands out loglan(1960) - a language based on formal logic, in which every statement must be understood in a unique way, and any ambiguity is completely eradicated. With its help, sociologist James Brown wanted to test the hypothesis of linguistic relativity, according to which the worldview of representatives of a particular culture is determined by the structure of their language. The test failed, since the language, of course, did not become the first and native language for anyone.

In the same year the language appeared linkos(from Latin lingua cosmica - “cosmic language”), developed by the Dutch mathematician Hans Vroedenthal and intended for communication with extraterrestrial intelligence. The scientist assumed that with its help, any intelligent being would be able to understand another, based on elementary logic and mathematical calculations.

But most of the attention in the 20th century received artificial languages that exist within works of art. Quenya And Sindarin, invented by professor of philology J.R. Tolkien, quickly spread among the writer’s fans. Interestingly, unlike other fictional languages, they had their own history of development. Tolkien himself admitted that language was primary for him, and history was secondary.

J.R.R. Tolkien

from correspondence

It is more likely that “stories” were composed in order to create a world for languages, rather than vice versa. In my case, the name comes first, and then the story. I would generally prefer to write in “Elvish”.

No less famous is the Klingon language from the Star Trek series, developed by linguist Marc Okrand. A very recent example is the Dothraki language of the nomads from Game of Thrones. George R.R. Martin, the author of the series of books about this universe, did not develop any of the fictional languages in detail, so the creators of the series had to do this. The task was taken on by linguist David Peterson, who later even wrote a manual about it called The Art of Inventing Languages.

At the end of the book “Constructing Languages,” linguist Alexander Piperski writes: it is quite possible that after reading this you will want to invent your own language. And then he warns: “if your artificial language aims to change the world, most likely it will fail, and you will only be disappointed (exceptions are few). If it is needed to please you and others, then good luck!”

The creation of artificial languages has a long history. At first they were a means of communication with the other world, then - an instrument of universal and accurate knowledge. With their help, they hoped to establish international cooperation and achieve universal understanding. Recently, they have turned into entertainment or become part of fantastic art worlds.

Recent discoveries in psychology, linguistics and neurophysiology, virtual reality and technological developments such as brain-computer interfaces may once again revive interest in artificial languages. It is quite possible that the dream that Arthur Rimbaud wrote about will come true: “In the end, since every word is an idea, the time of a universal language will come!<...>It will be a language that goes from soul to soul and includes everything: smells, sounds, colors.”

People have had this problem since ancient times"language barrier". They solved it in different ways: for example, they learned other languages or chose one language for international communication (in the Middle Ages, the language of scientists around the world was Latin, but now most countries will understand English). Pidgins were also born - peculiar “hybrids” of two languages. And starting from the 17th century, scientists began to think about creating a separate language that would be easier to learn. Indeed, in natural languages there are many exceptions and borrowings, and their structure is determined by historical development, as a result of which it can be very difficult to trace the logic, for example, of the formation of grammatical forms or spelling. Artificial languages are often called planned languages because the word “artificial” can have negative associations.

Most famous and the most common of them is Esperanto, created by Ludwik Zamenhof in 1887. “Esperanto” - “hoping” - is Zamenhof’s pseudonym, but later this name was adopted by the language he created.

Zamenhof was born in Bialystok, in the Russian Empire. Jews, Poles, Germans and Belarusians lived in the city, and relations between representatives of these peoples were very tense. Ludwik Zamenhof believed that the cause of interethnic hostility lies in misunderstanding, and even in high school he made attempts, based on the European languages he studied, to develop a “common” language, which would be neutral - non-ethnic. The structure of Esperanto was created quite simple for ease of learning and memorizing the language. The roots of the words were borrowed from European and Slavic languages, as well as from Latin and ancient Greek. There are many organizations whose activities are dedicated to the dissemination of Esperanto; books and magazines are published in this language, there are broadcast channels on the Internet, and songs are created. There are also versions of many common programs for this language, such as the OpenOffice.org office application and the Mozilla Firefox browser. The Google search engine also has a version in Esperanto. The language is supported by UNESCO.

Besides Esperanto, there are many other man-made languages, some widely known and some less common. Many of them were created with the same goal - to develop the most convenient means for international communication: Ido, Interlingua, Volapuk and others. Some other artificial languages, such as Loglan, were created for research purposes. And languages such as Na'vi, Klingon and Sindarin were developed so that characters in books and films could speak them.

What is the difference from natural languages?

Unlike natural languages, developed throughout the history of mankind, separated over time from any parent language and died, artificial languages are created by people in a relatively short time. They can be created based on the elements and structure of existing natural languages or "constructed" entirely. Authors of artificial languages disagree on which strategy best meets their goals - neutrality, ease of learning, ease of use. However, many believe that the creation of artificial languages is pointless, since they will never spread enough to serve as a universal language. Even the Esperanto language is now known to few, and English is most often used for international negotiations. The study of artificial languages is complicated by many factors: there are no native speakers, the structure can change periodically, and as a result of disagreements between theorists, an artificial language can be divided into two variants - for example, Lojban was separated from the Loglan language, Ido was separated from Esperanto. However, supporters of artificial languages still believe that in the conditions of modern globalization, a language is needed that could be used by everyone, but at the same time not associated with any particular country or culture, and continue linguistic research and experiments.

lizamartin wrote in December 4th, 2009In this essay, I would like to consider the problem of artificial languages: why do they appear, what purpose do they pursue, are they needed at all, and most importantly, how can we use them now? Are artificial languages a necessity, or is their creation a kind of game?

This question lies not only in the field of linguistics, but also in the field of psychology, because in essence the human desire to create an artificial language can be called a psychological phenomenon. And who knows, maybe it was the creation of artificial languages that became the first step towards the idea of creating artificial intelligence?

An idea as old as time

It is obvious that an artificial language, no matter how paradoxical it may sound, is a natural phenomenon. The very first artificial language about which information has been preserved was created by the philosopher Alexarchus in the 4th century BC. Alexarchus created the city of Ouranoupolis, in which he tried to create an ideal state. In Ouranoupolis, the philosopher-ruler equalized slaves and freemen and invited residents from different states to his city. It was then that the question arose about creating a new unified language for the inhabitants of Ouranoupolis. This is how the Uranian language appeared. This language was not a priori, because absorbed the roots of Eastern languages and the endings of words and grammatical categories of Western languages.

The city of Ouranoupolis is the birthplace of the first artificial language

Once it arose, the idea of creating an artificial language did not leave people. In the 2nd century, the Roman medical scientist Claudius Galen developed a system of graphic signs through which, in his opinion, different peoples could communicate. But his idea did not find support among his contemporaries.

In the Middle Ages, attempts to create artificial languages were very rare. Perhaps this happened due to the widespread use of Latin. Latin became the universal language for European civilization at that time. However, in the 12th century, Abbess Hildegard from Germany developed a liturgical language that was designed to delight the ears of everyone who prays. This language was created from a mixture of Aramaic, Greek, Latin, Northern French and West German.

Well, in the end, the Church Slavonic language is, by and large, the fruit of the mental labor of Cyril and Methodius, who relied on one of the dialects of the Bulgarian language.

Justification of the idea

From the 16th century, attempts began to appear to explain the nature of a rational international language. This was done by Thomas Campanella, Francis Bacon, and Rene Descartes.

Rene Descartes said that in an ideal artificial language there should be no irregular verbs, new words should be formed using prefixes and suffixes. Descartes also proposed to streamline language not only as a means of communication between all people, but also to streamline concepts, that is, to build a language based on classifications of concepts, to turn language into a tool of thinking, allowing one to draw logical conclusions and gain new knowledge.

Descartes said that by using such language, “peasants will be able to judge the essence of things better than philosophers do today.” At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, similar ideas formed the basis of Ithkuil, a language developed by the American linguist John Quijada.

Rene Descartes and John Quijada

In the 17th century, Jan Comenius, in his essay “The Structure of a Universal Language,” listed the basic principles of an international language: the root stock of common vocabulary should contain 200-300 words of Latin origin; grammatical categories must be economical and rational, without exception; the language should be easy to learn, harmonious, more perfect than existing ones.